Tech Crash: What’s Next?

By Thomas Kirchner of Camelot Portfolios

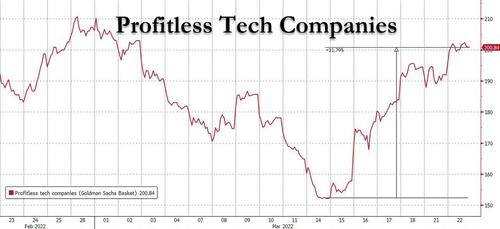

Last week’s short-lived tech rally pushed some unprofitable tech stocks up nearly 50%. As remarkable as such a move is, strong temporary moves to the upside are nothing unusual in a market that is crashing. And “crash” is the best description of what some areas of the technology sector are going through.

Tech stocks, as measured by NASDAQ, peaked on November 19, 2021. However, if we look at the subset of unprofitable growth stocks, former unicorns that have seen tremendous growth in their stock prices in recent years or former SPACs, then the peak in many of these stocks occurred a few months earlier shortly after the meme stock mania. Chinese tech stocks, in turn, peaked in late 2020 as the Chinese government clampdown on tech companies began.

Profitable vs. unprofitable tech

The distinction between profitable and unprofitable tech appears to have been a big driver of the performance differential since last year’s peak, and we believe this will become even more critical during the next two years.

For some firms, Covid has been an accelerator that brought long-term technology adoption forward. For others, it represented a one-time boost. For most tech companies, it seems to have been a combination of both: technology adoption was accelerated by Covid well above the long-term trend. With the return to normal, we expect to see a pullback toward the trendline. The exuberant enthusiasm for profitable stay-at-home-stocks has since turned into a hangover, with many of these firms giving back much of their multiple expansions. While the worst valuation excesses in some of these stocks have since been rectified by the market, we still would avoid these former market darlings.

Unprofitable tech firms have become an asset class of their own. Similarities to the dot-com boom of the late 1990s abound with a singular focus on growth and questionable business models. Even companies in the gig economy, and even real estate subletting firms have been classified as “tech” on the mere basis that these firms have an app as an interface with their customer. Many of these business models are, in our view, unsustainable.

For example, food delivery should be a straightforward cash business. Yet, not a single food delivery company we are aware of is profitable, even though employees often are not even earning minimum wage. The same applies to ride hailing apps, the other part of the gig economy that benefits from large valuations. These companies failed to turn a profit for years while growing. This would be plausible if newly acquired business takes time to become profitable. However, they still fail to become profitable when growth slows, and they should be able to harvest cash flow. The absence of such profits has us conclude that it is simply not possible to run many businesses in the gig economy profitably.

Chinese tech

We asked in December if Chinese tech stocks have bottomed. As we pointed out at the time, the clampdown on Chinese tech firms was caused by the power struggle in the CCP between President Xi’s clan, which advocates traditional authoritarian communism with limited market elements, and supporters of former Premier Jiang Zemin, who advocate further free-market reforms, a group that includes many tech entrepreneurs. It appeared at the time that Xi had consolidated his power to a point where a third term at the Congress in September was a given. However, after the Olympics turned out to be less of a PR success than anticipated for President Xi, it is not surprising that a new wave of power consolidation hits Chinese tech stocks with reports of a new attack on Ant Financial, whose shelved IPO was the beginning of the clampdown in November 2020, and ride-hailing app Didi.

It appears that the vigor of the adverse market reaction to the renewed tech clampdown took Chinese authorities by surprise. This explains Chinese officials’ comments, led by Vice-Premier Liu He last Wednesday, that authorities need to take a “standardized, transparent and predictable” approach to regulation [ii]. We believe that regulatory risks to Chinese tech stocks are now minimal because further attempts to consolidate power at the expense of financial markets would backfire and put the wisdom of the party’s leadership in question.

The main risk to Chinese tech stocks listed in the U.S, now comes from Washington and the potential for delisting. This can play out in two ways: Chinese tech companies delisted in the U.S. could simply relist in Hong Kong, as Didi plans to do. An OTC market for ADRs may develop in the U.S. The other option would be a going private transaction at a low valuation followed by a relisting in Hong Kong. With the sharp correction in the Hang Seng tech index, this has become less attractive unless the discount that can be had by the buyout group in U.S. markets becomes extreme. In such a scenario, we expect investors to exercise dissenters’ rights en masse.

SPAC crash

612 SPACs are currently looking for targets to take public through reverse mergers. This compares to about 4,000 companies currently traded publicly in the U.S. If each SPAC were successful, the number of publicly traded companies would expand by nearly 15% within the next two years after having declined from 5,500 in the 20 years from 2000 to 2020. We expect that a large number of SPACs will liquidate without a merger, which will result in the sponsors losing their investment. Sponsor capital will provide the yield on investor cash held in the SPAC’s trust account. We estimate the potential transfer of sponsor equity to public SPAC investors at up to $3bn.

The desperation of SPAC sponsors to get a deal done so that they do not lose their investment shows itself in the large number of questionable businesses models that SPACs have taken public.

Too many former SPACs fall into the category of lossmaking tech companies. Without the ability to raise new capital, their market value will eventually fall below the cash on their balance sheet, while they burn through cash. We anticipate seeing a re-run of the early 2000s, when activists acquired controlling stakes in these fallen angels at steep discounts to cash on the balance sheet, took control of the board and then simply liquidated the firms and distributed the cash. For many investors, that was the best outcome compared to letting the companies burn through the remaining cash.

The tech crash offers interesting opportunities for shrewd investors, even on the long side. As always, caveat emptor.

Tyler Durden

Wed, 03/23/2022 – 08:30