UK To Change Definition Of Debt So It Can Add $90 Billion More

Back in Sept 2022, the UK financial system almost collapsed when the bond market vigilantes woke up from a decade long slumber and in response to the tax-cutting mini-budget by former PM Liz “did not outlast the lettuce” Truss, sent yields soaring, the pound crashing and sparked a firesale of the country’s rate sensitive securities, forcing the BOE to resume QE virtually overnight as a buyer of last resort was desperately needed. It was a vivid reminder just how fake and unstable the global financial system has become if one just pulls the curtain on the unlimited daily supports from central bankers, and better yet, it was a teachable lesson why assets can never again drop: because if they do, it means central banks are no longer micromanaging the entire market and an epic crash is inevitable.

Long story short, the UK learned its lesson and the last thing it would ever do again is get perilously close to admitting the truth, which is that it is exclusively reliant on the debt market to fund its marginal deficit spending. Which, however, would mean two things: i) it would somehow have to convince the market it has much more debt capacity than it currently does, i.e. changing the definition of debt, and ii) it would need to actually do the right thing (something it has to do since unlike the US it doesn’t have a reserve currency to punch around) and either boost taxes or cut back spending.

That’s precisely what is about to happen.

Chancellor of the Exchequer Rachel Reeves, the UK’s equivalent to the Treasury Secretary, has embraced a fiscal overhaul that could allow the UK to borrow as much as £70 billion ($91 billion) more over the next five years by changing the very definition of debt, as the government defended a budget that looks increasingly likely to tax investors.

As Bloomberg reports, at next week’s budget, the government “will be changing the way that we measure debt” to a new arrangement that will “free up money to deliver a long-term return to our country and taxpayers,” Reeves told reporters on Thursday in Washington, where she was attending the IMF’s annual meetings.

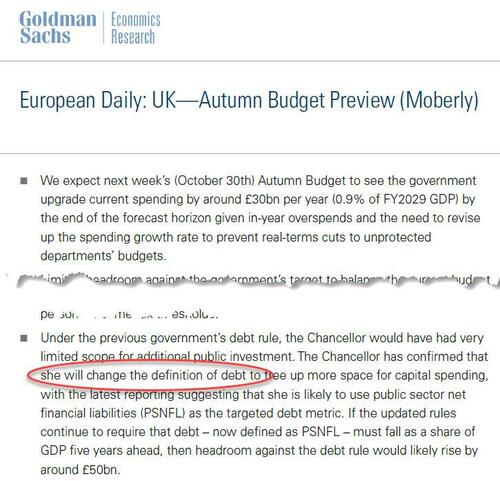

And yes, we are literally talking about “changing the definition of debt” as Goldman explained in its Budget preview note (available to pro subscribers).

Her comments confirm local reporting that her budget “will include a new method for assessing the UK’s debt position – a move that will permit the Treasury to borrow more for long-term capital investment.” The change to the debt rule will be welcomed by the IMF, which says spending on UK infrastructure projects should be ringfenced as the government seeks to repair the damage to the public finances caused by the pandemic and the cost of living crisis.

At the Budget next week, I will show that we have a choice between investment versus decline.

I am choosing to invest in Britain so we can turn the page on fourteen years of decline and start making the country better off. https://t.co/aMheErGtdf

— Rachel Reeves (@RachelReevesMP) October 24, 2024

Reeves’ remarks on Thursday confirmed speculation that had mounted ahead of the Oct. 30 budget that she would alter her fiscal rules, and in particular the measure of debt that guides them, in order to allow Britain’s new Labour government to make those investments.

At the budget, she’s planning to set out two fiscal rules to set the tone for Labour’s first term in office since 2010:

The first rule requires her to pay for day-to-day spending out of taxes. To meet that rule with sufficient headroom to give her flexibility in a crisis, Reeves needs about £40 billion from tax rises and welfare cuts. She refused to be drawn on which taxes will rise but there is widespread expectation that employers will pay more national insurance and that capital gains and inheritance taxes will rise. Income tax thresholds may also be frozen for two more years. That could raise about £20 billion, according to analysis by think tanks such as the IFS, Resolution Foundation and the Institute for Public Policy Research.

The second rule is that debt must be falling in the fifth year of the official forecast. The measure of debt has yet to be defined but is widely expected to be “public sector net financial liabilities,” which captures the value of assets created alongside the cost of any investment, effectively removing the debt from the books. As a result, the National Wealth Fund and GB Energy would have more scope to invest. Compared with the existing measure of “public sector net debt excluding the Bank of England,” PSNFL will give Reeves £53 billion of additional annual borrowing headroom. Under PSNFL, she would meet her rule with three years to spare.

Speaking to reporters, the chancellor hinted she may make the debt rule tougher by moving from a rolling five-year target to a fixed date of 2029-30. She said: “It is important to do that in the course of the parliament because otherwise it’s always in the future and it never actually gets met.”

By targeting the fiscal rules, and by literally changing the definition of debt, the chancellor is trying to free up as much capital to invest as possible to eliminate the need for further painful tax hikes, because apparently the market is so stupid it can’t figure out what she plans on doing. Reeves said she didn’t want to see public investment fall, as currently projected, to 1.7% of gross domestic product by 2029 from 2.5% now. “We would be embracing the path of decline,” she said.

Reeves is trying to strike a balance between fiscal prudence to keep financial markets on side while increasing investment in roads, schools and other public infrastructure, to drive up economic growth and tax revenues while also ending austerity in public services.

“The reason we’re doing that is because there are massive opportunities to invest in Britain,” Reeves said in a Sky News interview. “To get the growth and jobs for the future here for the UK, it’s not possible under the current rules.”

Maintaining investment spending at 2.5% of GDP across the parliament would cost a cumulative £70 billion, according to Ben Zaranko, a senior research economist at the Institute for Fiscal Studies. Reeves said she would set out the path for public sector net investment in next Wednesday’s budget.

At the IMF, the chancellor told fellow finance ministers that everything Labour plans will be “built on the rock of economic stability”, by which she supposedly means changing definitions of core financial concepts.

Apparently that was not lost on the debt market either, and in an ominous sign, gilt prices wobbled this week at news of the scale of the potential borrowing, with the spread between gilt yields and German bunds widening since a report in the Guardian newspaper late Wednesday. The yield on 10-year gilts rose on Thursday, widening the spread over equivalent German notes to 199 basis points, the highest in a year. As John Authers notes, the spike in gilts means that the spread of gilt yields over French OATS is back above its level when France’s Emmanuel Macron made his ill-fated decision to call a snap election back in June: “If not an event on a par with the bond market revolt that greeted former Prime Minister Liz Truss’s mini-budget in 2022, this is still a big deal”, but don’t worry, it will get there.

Adding insult to injury, before Reeves announced her plan to borrow more, the International Monetary Fund this week supported the prospect of Britain moving to a debt rule allowing more investment but also warned that UK debt is already on an unsustainable upward trajectory, which it is explicitly encouraging.

To give markets confidence that Labour will not use all the available borrowing headroom (spoiler alert: it will, and then some), Reeves said “guardrails” will ensure that “any taxpayer money invested will get a return for taxpayers.” The government will also “work with the National Audit Office and the Office for Budget Responsibility to make sure that all those investments are properly validated,” she said. “In terms of markets, that’s why I think these guardrails are important.”

Zaranko said that “the key constraint” on the government’s borrowing for investment will now be its “ability to find good projects and the construction sector’s ability to deliver them,” rather than its fiscal rules.

And while the Labour government is about to change the definition of debt to raise more of it, it will also change the definition of “working people” to tax more of them.

At an annual meeting of Commonwealth heads in Samoa, Prime Minister Keir Starmer was challenged over the definition of working people — who his government has vowed will avoid tax rises in Wednesday’s economic plan.

People who own assets are not “working people”, he said, adding that the type of person he intended to protect was someone who “goes out and earns their living, usually paid in a sort of monthly check” but who does not have the ability to “write a check to get out of difficulties.” One measure being weighed by Reeves is increasing the capital gains tax levied on entrepreneurs when they sell their businesses, according to people familiar with the matter.

The shift in the fiscal rules and hints of a forthcoming tax hike on investors come as the Treasury tries to scrape together enough cash to reverse a decline in spending on infrastructure, and keep its manifesto pledge of boosting growth in the UK economy.

Alas, Starmer’s comments will add to fears that Labour – along with every other socialist/progressive government in Europe and elsewhere – will prompt a rapid flight of the wealthy out of the UK. Reeves has pledged that those with the “broadest shoulders” will have to bear the burden of greater taxes, but many have already made plans to leave. One investor who moved last month to Lugano from London to avoid increased levies on his wealth, Christian Angermayer, told Bloomberg at the time that “every non-dom I know has left or is about to leave,” referring to non-domiciled residents who are currently given some tax breaks on assets held overseas.

In other words, the UK is about to dig itself into a far deeper hole as all those it plans to tax, well, flee to Dubai.

Meanwhile, speculation on what the budget might hold has also been weighing on households more broadly. Consumer confidence edged lower this month, according to a closely watched survey, as Britons became more downbeat about the economy, and with reason: because the tempest that is about to hit the UK will make the mini-budget disaster seem like a jolly dress rehearsal.

More in the Goldman UK Autumn Budget Preview report available to pro subscribers.

Tyler Durden

Fri, 10/25/2024 – 14:00