The Need To Breed

By Russell Clark of Capital Flows and Asset Markets

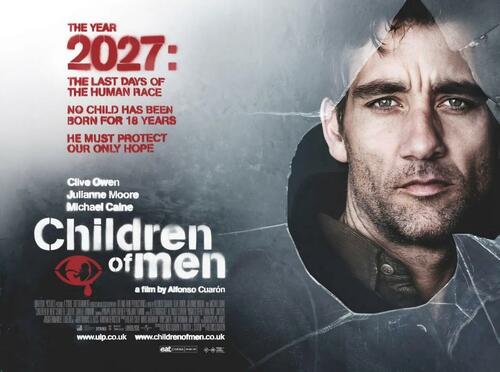

I like my sci-fi films. Tiktoks about the best sci-fi films of all times often recommend 2006 film Children of Men . I didn’t remember it as a truly great film when I first watched it – so decided to watch it again. On rewatching – I do think it’s a masterpiece. The long takes are mind-boggling. And I think the finale and the theme of movie was more moving now that I am a father myself. Recommended.

If you have not seen it – it imagines a future where a world-wide pandemic has rendered the world infertile. Strangely prescient, and yet also wrong. In “Children of Men” the collapsing fertility leads to a collapsing society. Japan has been the poster child of falling population, and yet societal collapse has yet to happen. Unsurprisingly, older societies tend to prefer order to chaos.

The IMF population numbers above assume fertility rates continue to remain low. One theme of “Children of Men” is that we as a species, want to procreate. That there are 8 billion of us pretty much proves that we are genetically predisposed to having children. While I understand the arguments that some people make that the world is overpopulated and not having children is a logical choice -again by definition within a generation or two groups that choose to have children should dominate the population. We have seen this in action in Israel, where the ultra-orthodox Jews now make up much higher proportion of children in Israel than their total share of the population, and are the most rapidly growing part of Israel’s population.

All of this makes me think that rising populations, and higher fertility rates are a secular theme, while the low fertility rates we have seen later are a “cyclical” story. So what could be driving this cyclical story? First of all – capitalism is not good for fertility. The shift right wards in global politics that happened in the 1970s marked the end of the baby boom. For countries in Eastern Europe that moved rapidly from Socialism to capitalism in 1990s have seen even more dramatic falls in fertility even as incomes have soared. It seems to me falling incomes relative to asset prices encourages falling fertility rates. Or if you can’t feed them, don’t breed them. But the fact of capitalism is that the owners of capital will constantly seek to pay the least amount possible for labour. What we have seen from 1970s to 2010, was that unemployment in the US was higher that it was in the 1960s. In recent years, initial jobless claims have remained remarkably low. If the average worker begins to feel more secure about the future, expect fertility rates to rise.

The second part of the argument is technological. Families are choosing to start having families later in life. This naturally reduces the window when it is possible to have children, leading to a falling fertility rate. My argument is that technology is improving to allow women to have healthy babies later in life. The biggest factor driving this is that realisation that the success of IVF is not tied to the age of the mother, but the age of the eggs and embryos.

As more and more women realise that freezing eggs before the age of 30, can give the opportunity to have a successful birth in your 40s, technology is increasing the window where women can have children. That’s the theory, but is it happening? The evidence so far is mixed. Denmark has by far the most liberal and supportive policies on IVF. When policy was changed a few years ago, there was a significant uplift in births, but recent data is showing that coming off again.

The problem is that the process of pregnancy is quite long, especially if you are using IVF. From deciding to undertake IVF, through to actually giving birth can be three or four year process. Another country I look at is Australia. Australia has universal healthcare, and published good statistics. Despite being a nation built on immigration, Australian fertility rates have been falling steadily.

As can be seen below, Australian mothers are becoming older. You can also see that the baby boom was driven by mothers suddenly becoming younger after World War II – a trend that has more than completely reversed. Baby boomers was a demographic aberration that is now passing through the system.

Australia combines its statistics on IVF (or Assisted Reproductive Technology – ART) with New Zealand. ART births have continued to climb, and are now nearly 6% of all live births.

But as mentioned, live births are at the tail end of a decision made two or three years earlier. Fortunately we can get statistics in Australia on the number of IVF cycles. These do not necessary correlate to births in a year or two, as cycles to freeze eggs could be far into the future. But it does show the intention to have children. As in the UK, freezing cycles are becoming more and more common.

So do we face a fertility crisis? I doubt it very much. In fact if was to right a sci-fi film about the future, the story would be more along the lines of as the baby boomer generation died out, demand for labour soared, as the working population declined. Rising political power saw government direct more spending to the young, which raised disposable incomes. Families could start to afford to have more children, and many women who froze the eggs in their 20s take the opportunity to have one more child in the late 30s and early 40s. Populations shifted younger again, and political parties actively courted the votes of the young and families, creating a virtuous cycle of pro-natal policies. This makes far more sense to me than predictions that Japanese, Korean populations will fall by half. Extrapolation without analysis is the bane of modern economics – it is such simplistic thinking. Mentally, it makes economists children, not men.

Tyler Durden

Tue, 10/01/2024 – 10:15