Scholars Create App To Track “Offensive,” “Harmful” Street Names

By Micaiah Bilger of The College Fix

‘Discriminatory beliefs are woven into everyday spaces,’ professors say

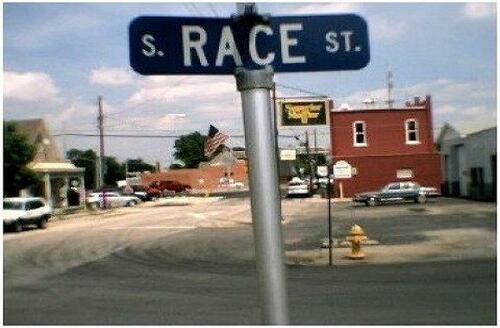

A group of Spanish scholars has created a new app that they say will help identify racially “offensive,” “harmful” street names and “repair past wrongs.”

Geography Professors Derek Alderman at the University of Tennessee and Joshua Inwood at Penn State University described the STNAMES LAB app as an “important education tool” in a recent article at The Conversation. Project leader Professor Daniel Oto-Peralías at Universidad Pablo de Olavide in Spain also co-wrote the article.

The app “will help communities understand how discriminatory beliefs are woven into everyday spaces and the harm caused by offensive names,” the professors wrote.

“After tracking a few of America’s most contested place and institution names, we believe the app will help people see the changes necessary to recognize and repair past wrongs in street naming,” they wrote.

The STNAMES LAB app allows users to search for specific terms used in street names in North America and western European countries, and provides exact locations and downloadable spreadsheets of the streets.

On the North American map, the professors said they searched for names with the words “savage” and “squaw”:

We found 429 streets scattered across 47 states with a name containing the word “sq—.”

Although “sq—” originated in the Algonquian language, European settlers corrupted and misused the word in reducing Native American women to a simplistic and sexualized image. Being called “sq—” is still a painful daily reality for Indigenous women. Many of them say the term injures their self-image and sense of belonging. …

We found 415 roads in 46 states using the word “savage” in their name.

The professors said the app reveals how “pervasive a problem” these street names are in America. Names “can transmit harmful messages that misrepresent the history and identity of minority communities,” they wrote.

They expressed hope the app will help initiate change, writing, “When hurtful names are removed from roads, some members of oppressed communities describe how the spirit or feeling of places can change and allow healing to begin.”

Scholars who created the app expressed similar thoughts, writing on the project website, “The frequent controversies occurring around the naming and renaming of streets, as well as the use that political regimes make of street names to inscribe a certain ideology into the urban landscape testify their symbolic power.”

Removing names deemed to be offensive has become more common in recent years among higher education institutions.

In May, Boston University announced plans to strip Plymouth Colony leader Myles Standish’s name from one of its dormitories after faculty accused him of “terrible acts against the native people,” The College Fix reported.

Meanwhile, a Johns Hopkins University board is considering removing the name of President Woodrow Wilson from a fellowship program, The Fix reported.

Other examples include “Star Spangled Banner” author Francis Scott Key, former U.S. Chief Justice John Marshall, scientist Carl Linnaeus, and General Robert E. Lee’s horse.

Tyler Durden

Fri, 08/16/2024 – 14:20