What ‘Project 25’ Says About The Fed

Authored by Jonathan Newman via The Mises Institute,

Mandate for Leadership 2025 is an unofficial blueprint for a potential conservative administration, published by the Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025. Donald Trump has distanced himself from the project, even though many people associated with his first term as president contributed to the document.

It’s billed as “The comprehensive policy guide for a new conservative president, offering specific reforms and proposals for Cabinet departments and federal agencies, pulled from the expertise of the entire conservative movement.” Paul Dans, the Project 2025 Director, says that the project aims “to deconstruct the Administrative State.”

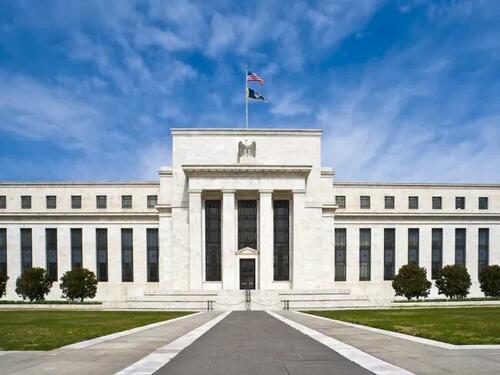

Chapter 24 of the 922-page document is on the Federal Reserve. It was authored by Paul Winfree, Distinguished Fellow in Economic Policy and Public Leadership at The Heritage Foundation.

The chapter is decidedly anti-Fed – it calls for abolishing the Fed altogether and returning to a commodity-backed money – but it also suggests some more politically palatable reforms that would merely limit the Fed, in case the more radical measures prove to be infeasible. Winfree lists the proposals “in decreasing order of effectiveness against inflation and boom-and-bust recessionary cycles.” Free banking (which entails abolishing the Fed), and a return to commodity money are listed first.

Overall, the chapter presents a great, albeit brief, critique of government intervention in money and banking. It blames the Fed for exacerbating the cycle of booms and busts, inflating away the value of the dollar, enabling exorbitant deficit spending by the federal government, picking winners and losers in financial markets, and expanding its own power with each crisis.

From a Misesian-Rothbardian perspective, it has a few Friedmanite flaws. But assuming Donald Trump isn’t going to read and adopt Rothbard’s views in What Has Government Done to Our Money?, this is much better than the tepid, Fed-embracing advice from “right-wing Keynesians” during the 80s and 90s. (See “Clintonomics: The Prospects” in Making Economic Sense for more on them.)

The influence of Friedman’s monetarism is not just in the third-, fourth-, and fifth-best policy compromises. The chapter begins in error: “Money is the essential unit of measure for the voluntary exchanges that constitute the market economy.” The idea that money is a unit of measure leads to a host of errors in monetary theory, leading to the conclusion that the purchasing power of money should be stabilized.

In fact, it was this idea that led to the creation of the Fed in the first place. Winfree acknowledges this: “The Federal Reserve was originally created to ‘furnish an elastic currency’ and rediscount commercial paper so that the supply of credit could increase along with the demand for money and bank credit.” Winfree says that the Fed’s ability to stabilize the purchasing power of the dollar is hindered by the full employment side of the Fed’s dual mandate and by discretionary, as opposed to rules-based, monetary policy. Instead of attacking the Fed on more fundamental grounds, namely that the original justification for the Fed was fallacious, Winfree accepts this justification and says that Fed doesn’t do a good job at this task.

The chapter also mentions Friedman’s diagnosis of what prolonged the Great Depression, but without citing him. According to Friedman, the Federal Reserve failed to prevent a collapse in the money supply from 1929 to 1933, and this is what caused what would have been a “garden-variety recession” to turn into the Great Depression. Winfree alludes to this diagnosis in more general terms: “the Great Depression of the 1930s was needlessly prolonged in part because of the Federal Reserve’s inept management of the money supply.” Of course, those who have read Rothbard’s America’s Great Depression know that it was the Fed-enabled monetary expansion in the 1920s that led to the inevitable bust, and that the depression of the 1930s was prolonged due to the host of interventions by Hoover and FDR. Bank failures and the concomitant collapse of money and credit actually help the adjustment process through the liquidation of mismanaged banks and by realigning the supply of credit with real savings.

The influence of Friedman and the Chicagoites is most apparent in the policy proposals offered as alternatives to ending the Fed. Friedman’s “K-Percent Rule” is listed after the proposal to return to a commodity standard. The “K” refers to a fixed rate of growth in the money supply—Winfree offers 3 percent per year as an example. The idea is to take central bank discretion completely off the table, much like the other proposed rules: the inflation-targeting rule (which Winfree acknowledges is already somewhat in effect at the Fed), the Taylor Rule, and the Nominal GDP Targeting Rule.

An important problem with all of these rules (aside from the fact that discretion can be good) is that they are arbitrary. Why a 3 percent fixed rate in money supply growth? Why should we have a 2 percent price inflation target? What weights should be applied in the Taylor Rule? Why should nominal spending be stabilized? To see why any explicit or implied target is arbitrary, consider what we would see in a progressing unhampered market economy.

In such a progressing economy, we would probably have steady (but not fixed) price deflation primarily due to the increased production of goods and services. This expectation accords with historical experience, especially the 19th century: “throughout the nineteenth century and up until World War I, a mild deflationary trend prevailed in the industrialized nations as rapid growth in the supplies of goods outpaced the gradual growth in the money supply that occurred under the classical gold standard.”

But even this is not grounds for a monetary policy rule that targets some fixed rate of price deflation, for the same reason we shouldn’t fix the price of anything based on what we assume is a natural trend. The economy is in constant flux as values change, the stock of known natural resources changes, technology is invented, and savings preferences change, among countless other factors. This is why Mises referred to stabilization policy as “an empty and contradictory notion” (Human Action, p. 220). To Winfree’s credit, he acknowledges that without a central bank, “the norm is for the dollar’s purchasing power to rise gently over time, reflecting gains in economic productivity.” It seems that this point is lost, however, once the monetary policy rules are discussed.

I’m not against taking incremental steps to chip away at State power, but the proposed rules seem more like side-steps or steps backward. For example, if the Fed were explicitly committed to the Taylor Rule, this would probably bolster the perception that the Fed is an impartial, scientific agency using sophisticated models and tools to manage the macroeconomy.

These issues, and a few other minor points (like the claim that fiscal policy is ok if it is “timely, targeted, and temporary”) keep me from giving this chapter an A+. But I wholeheartedly agree with the anti-Fed spirit and statements like the following:

A core problem with government control of monetary policy is its exposure to two unavoidable political pressures: pressure to print money to subsidize government deficits and pressure to print money to boost the economy artificially until the next election. Because both will always exist with self-interested politicians, the only permanent remedy is to take the monetary steering wheel out of the Federal Reserve’s hands and return it to the people.

It seems to me that all the alternative reform ideas involving “rules-based monetary policy” are moot because of these political pressures. Rules are easily bent and abandoned when political winds change. We should just remove the cancer and replace it with nothing.

Tyler Durden

Sat, 07/27/2024 – 15:10