Two Tidbits Of Timeless Political Wisdom From Machiavelli

Authored by Charles Hugh Smith via OfTwoMinds blog,

“Generosity” funded by debt or currency devaluation is the opposite of generosity: it is the ultimate taking.

Now that the air is thick with the burned-rubber stench of politics, let’s consider two tidbits of timeless political wisdom from Machiavelli. Though often-maligned as the dark Lord of amoral cunning, my re-reading of Machiavelli’s The Prince (completed in 1514, published after his death in 1532) reveals Mr. M. as a practical sort, not so much a promoter of devilish amorality as an observer wise to the vagaries of power.

Let’s start with a famous excerpt from Chapter Six. The first is a translation in the modern vernacular; the second is an older more literal translation.

The Prince (PDF):

Here we have to bear in mind that nothing is harder to organize, more likely to fail, or more dangerous to see through, than the introduction of a new system of government. The person bringing in the changes will make enemies of everyone who was doing well under the old system, while the people who stand to gain from the new arrangements will not offer wholehearted support, partly because they are afraid of their opponents, who still have the laws on their side, and partly because people are naturally skeptical: no one really believes in change until they’ve had solid experience of it. So as soon as the opponents of the new system see a chance, they’ll go on the offensive with the determination of an embattled faction, while its supporters will offer only half-hearted resistance, something that will put the new ruler’s position at risk too.

The literal translation:

The Prince (PDF):

And it ought to be remembered that there is nothing more difficult to take in hand, more perilous to conduct, or more uncertain in its success, than to take the lead in the introduction of a new order of things, because the innovator has for enemies all those who have done well under the old conditions, and lukewarm defenders in those who may do well under the new. This coolness arises partly from fear of the opponents, who have the laws on their side, and partly from the incredulity of men, who do not readily believe in new things until they have had a long experience of them. Thus it happens that whenever those who are hostile have the opportunity to attack they do it like partisans, whilst the others defend lukewarmly, in such wise that the prince is endangered along with them.

What Mr. M. is describing here is the immense incentive of those who have been well-served by the status quo to fight tooth and nail to defend its current configuration to maintain their share of the gravy train. Those who fear losing will fight far more vociferously than those who hope to gain from an uncertain and risky change of regime.

This generates what I’ve termed doing more of what’s already failed for if the status quo was actually functioning as wonderfully as its defenders’ claim, then there would be little need to defend it against calls for a new arrangement.

What Mr. M. didn’t describe is the helping hand of collapse: when the status quo finally unravels, those it enriched will embrace the magical-thinking delusion that it can be restored in some sacrifice-free fashion, and that because they benefited so handsomely, everyone else should support this restoration.

But it’s too late for a painless restoration, and so the defenders of the old order eventually give way and bitterly accept the necessity for a new arrangement. Short of systemic breakdown, those who have been enriched by the status quo will actually hasten its demise, for in their desperation to cling to “what’s good for me is good for everyone,” they will devalue the currency, borrow sums that can never be paid, and deploy other artifices to prop up an unsustainable status quo.

Which brings us to the second tidbit of timeless wisdom: the enduring advantage of frugality over liberality. The word “mean” in this contexts refers to frugality, not cruelty, and “liberal” refers to generous spending, not Progressive politics. We start with the modern vernacular translation again:

Since a ruler can’t be generous and show it without putting himself at risk, if he’s sensible he won’t mind getting a reputation for meanness. With time, when people see that his penny-pinching means he doesn’t need to raise taxes and can defend the country against attack and embark on campaigns without putting a burden on his people, he’ll increasingly be seen as generous — generous to those he takes nothing from, which is to say almost everybody, and mean to those who get nothing from him, which is to say very few. In our own times the only leaders we’ve seen doing great things were all reckoned mean. The others were failures.

Nothing consumes itself so much as generosity, because while you practice it you’re losing the wherewithal to go on practicing it. Either you fall into poverty and are despised for it, or, to avoid poverty, you become grasping and hateful. Above all else a king must guard against being despised and hated. Generosity leads to both. It’s far more sensible to keep a reputation for meanness, which carries a stigma but doesn’t rouse people’s hatred, than to strive to be seen as generous and find at the end of the day that you’re thought of as grasping, something that carries a stigma and gets you hated too.

The literal translation:

Therefore, a prince, not being able to exercise this virtue of liberality in such a way that it is recognized, except to his cost, if he is wise he ought not to fear the reputation of being mean, for in time he will come to be more considered than if liberal, seeing that with his economy his revenues are enough, that he can defend himself against all attacks, and is able to engage in enterprises without burdening his people; thus it comes to pass that he exercises liberality towards all from whom he does not take, who are numberless, and meanness towards those to whom he does not give, who are few.

We have not seen great things done in our time except by those who have been considered mean; the rest have failed.

And there is nothing wastes so rapidly as liberality, for even whilst you exercise it you lose the power to do so, and so become either poor or despised, or else, in avoiding poverty, rapacious and hated. And a prince should guard himself, above all things, against being despised and hated; and liberality leads you to both. Therefore it is wiser to have a reputation for meanness which brings reproach without hatred, than to be compelled through seeking a reputation for liberality to incur a name for rapacity which begets reproach with hatred.

In other words, limited-spending frugality allows the ruler to be generous to the many by keeping taxes low. While generosity initially generates a warm and fuzzy feeling for the ruler, the eventual result of opening the spigots of the money reservoir is either the bankruptcy of the currency–the ultimate rapacity, as everyone’s money is consumed in a great bonfire–or much higher taxes imposed as the only means to stave off insolvency.

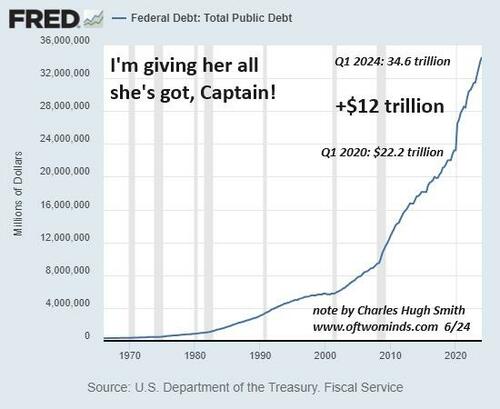

Here is Federal debt–a parabolic increase in “generous” spending, “generous” until the consequences show up:

Here is total public-private debt: Everybody’s borrowing and spending “generously” until the banquet of consequences is served, and Mr.M.’s rapacity which begets reproach with hatred is the main course.

In summary: “generosity” funded by debt or currency devaluation is the opposite of generosity: it is the ultimate taking. There is indeed an amoral cunning to this fake “generosity” and the temporary illusion of “wealth” it creates, but Mr. M. is not promoting this artifice, he is making the case against it.

* * *

Tyler Durden

Tue, 07/23/2024 – 07:20