Who Gets The House In The Divorce Between The United States And China

Submitted by Brent Johnson of Santiago Capital.

Through a range of measures, counter measures and sheer beligerence on both sides, the United States and China are going through a divorce of epic proportions.

The initial signs of serious fracturing in the relationship occurred following the outbreak of COVID-19, although the Trump administration’s hardened stance on bilateral trade was a clear precursor, as he played to a parochial audience. Blame on the source of the global pandemic soon morphed into increasing intolerance of trade issues that were once irritating, but were fast becoming non-negotiables. Tariffs, intellectual property and trade imbalances became a bipartisan issue in Washington DC, one of the few areas of agreement between the political parties.

Regardless of the true cause, it is unprecedented that such large economies are seeking to reverse the ties that have grown since China’s admission to the World Trade organization in 2001. The USSR and the US had barely traded with each other during the Cold War, so there were not as many economic complexities to resolve as they grew apart following World War II. As such, our current reality is a highly unusual situation, given the sheer size of the respective economies and the amount of trade that takes place between the two countries.

One area of this global divorce that we feel deserves special attention is the respective housing markets of not just the US and China, but also other western housing markets, more specifically Canada and Australia.

Residential real estate is typically regarded as a localised asset class rather than a global one. Favorable credit conditions are behind any real estate boom and these credit conditions are primarily determined by local interest rates and lending standards. However, we believe that local real estate markets have been greatly influenced by global trends.

In the case of the US sub-prime boom of the early 2000s, lax lending standards saw sub-prime lending expand from an historical average of around 3% of total home lending to in excess of 20% by 2007. While this served to achieve an increase in total US home ownership of a few percentage points, such profligate lending eventually led to unprecedented home loan defaults, and a near collapse in the global financial system.

We are currently seeing a similar pattern play out in China. Following China’s admittance into the World Trade Organization in 2001, development and trade skyrocketed. Competition for lending was magnified which drove down borrowing costs, which then led to a booming real estate market. The Chinese property market was estimated to have reached a value of USD $50 trillion, making it easily the largest asset market in the world, being twice the size of the US economy.

Continue reading the report at the Macro Alchemist website.

This wasn’t just to the benefit of China.

The higher Chinese property prices went, the more wealth was generated that could then be invested in other property markets around the world. And it is well documented that a flood of money also left China over the past few decades, bound for the residential housing markets of the US, Canada, Australia and others. As globalization expanded, and interest rates fell throughout those markets as well, these housing markets grew with it.

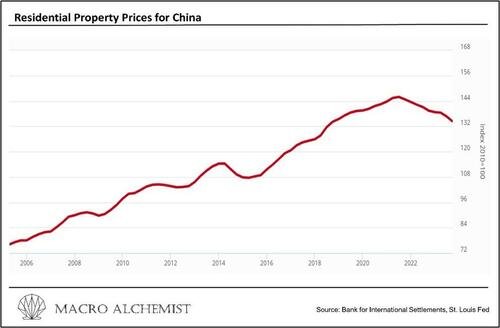

But just as it was in the US 18 years ago, this Chinese residential boom, funded by mountains of cheap credit, was unsustainable to any who chose to look at it for what it was. And over the last 10 years, the Chinese property market has fallen precipitiously.

While this chart below displays this fall, it doesn’t come close to telling the whole story, because this only reflects the price of residential property that has been finished and sold. The true demolition of this asset class will be further revealed below.

Contributing to China’s real estate downturn is the fact that globalization is now reversing. And the incredible amount of excess property capacity that has been constructed in China is putting downward pressure on local property prices, which continue to decline in concert with China’s demographic cliff.

While trade wars and capital controls have manifested through the Chips Act, the Inflation Reduction Act and other sanctions from both sides of the ideological divide, little consideration has been given to the resulting impact on global property markets. We have already seen the impact of the thirst for yield that arose from negative and zero interest rates on commercial real estate in the US. Investors from around the world who sought yield refuge in commercial real estate are now counting the cost.

While the residential real estate markets of the United States, China, Australia, and Canada share some common features, such as reliance on mortgages for funding, they also exhibit significant differences in terms of market dynamics, sources of funding, types of funding, and levels of funding.

These variations reflect the unique economic, social, and regulatory contexts of each country’s housing market.

But the property markets in China, the US, Canada and Australia are also connected in many ways:

China’s property market grew to an unprecedented size, creating unprecedented paper wealth.

The resulting wealth generation saw an equally unprecedented Chinese appetite to take capital outside of the reach of the Chinese government, investing in houses within liquid (Western) jurisdictions with strong rule of law.

Commodity exporting economies such as Canada and Australia further benefitting from supplying China’s construction boom.

The Chinese property juggernaut absorbing massive foreign inventory at inflated prices, forcing Western locals to pay up in their own markets to compete against Chinese investors.

Historically low global interest rates, against a backdrop of globalization, enabling property markets to rise in unison.

Globalization enabling free capital flow between these nations.

The more debt the Chinese property market accumulated, the more the need for debt arose in the Western property markets in order for local buyers to compete with Chinese buyers

In essence, the growth and linkages of these markets were not primarily driven by a reach for yield, or purely local speculative frenzy. Rather, it was a result of the incredible growth in global GDP attributed to the Chinese real estate market, and as a refuge for newly created wealth leaving China. And it has been a one-way flow, given foreigners cannot invest in Chinese housing.

We believe the Chinese real estate market has more downside to come.

And we do not believe the pain involved will be contained to China.

So as the US and China move forward with divorce proceedings, what happens if we are right regarding further Chinese housing distress?

What happens to other global housing markets that have been the beneficiaries of Chinese investment?

What happens if Chinese demand for housing in western markets disappears as the local wealth generation engine has stopped?

And what happens if further Chinese wealth destruction necessitates Chinese liquidation of foreign housing ownership?

In this divorce, who gets the house?

Tyler Durden

Tue, 06/25/2024 – 08:15