When “Making It” Becomes Hopeless

Authored by Charles Hugh Smith via OfTwoMinds blog,

No wonder so many people devote themselves to curating an artificial digital representation of themselves that they reckon is worthy of recognition and status.

What does it take to “make it” in today’s economy? As described in Withdrawing from the Rat Race Is Going Global, the world has changed in fundamental ways that have made it much more difficult to “make it” into the ranks of the middle class, and even harder to claw one’s way into the higher reaches of the economic order, i.e. the top 10%.

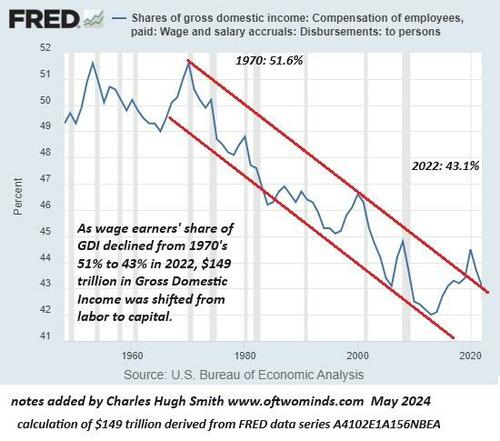

In summary, developed economies have been stripped of secure, well-paid manual-labor work, the purchasing power of wages has declined, prices of assets such as homes have skyrocketed out of reach and the mass overproduction of elites (those with college diplomas and advanced degrees) has created a winner-take-all competitive pressure cooker with few winners and an abundance of also-rans.

In other words, the work-a-day world has become far more complex and far more demanding than it was two generations ago. It’s not just making enough to pay the bills that’s more demanding; the work is more demanding, as is everyday life, which now demands far more shadow work–work we do to manage life’s complexities that we’re not paid for. Having children is far more expensive and demanding, too, as the competition for upper-middle class slots now starts in Kindergarten.

Many individuals do not have the armor and weaponry needed to enter the arena and survive the competition. It’s easy to dismiss them as “lazy,” but that’s not the issue. It’s also easy to dismiss them as snowflakes, young people who have been shielded from life’s rougher edges by overprotective parents, leaving them ill-equipped for the slings and arrows of modern life.

But this isn’t the issue, either. The real issue is the social and economic demands now exceed the carrying capacity of many people. Where it was possible to find a secure low-level job that could support a household and find a place in society’s pecking order two generations ago with limited social / work skills, now it’s essentially impossible: low-level work is insecure and too poorly paid to support a household, and it is viewed as demeaning and unworthy of respect.

How do humans respond when they’re viewed as worthless and they feel hopeless? In the Hollywood script, they pick themselves up, dust themselves off, gather a discarded shield and sword off the blood-soaked sand of the arena and go out and kick some derriere. (“Take that, nepo scum!”)

Many people manage to do this and we applaud their grit and determination. But not every individual wins in this battle. Many pick up the shield and the sword and are immediately trampled. They make a realistic assessment that they can’t possibly reach the lofty goals demanded of them, and so they are effectively excluded from what is now considered “normal life.”

This comment on a Reddit thread speaks to the increasing demands of “normal life”:

I obviously can’t speak for everyone, but I can give some insight based on my own social withdrawal: modern life is overwhelming. It feels like there’s a lot that’s expected of you. In many ways modern life is a giant competition for wealth and status, but instead of competing just within your community, you have to compete with millions of people all around the world. It feels daunting, if not impossible. Why compete in a contest you know you can’t win? It’s pointless, it’s a waste of time and energy. I feel very much like, “well, what’s the point?”

So they drop out of the competition. Maybe they take a part-time gig job, maybe they move back home to take care of a parent or grandparent, or they become a recluse.

Hikikomori–hiki, to withdraw–komori, inside–is an extreme form of voluntary social isolation from society. The term originated in Japan but the abandonment of conforming to the demands of society is not limited to Japan. Withdrawing from the demands of what passes for “normal life” is not limited to extremes of seclusion; it is a spectrum of withdrawal that includes giving up on striving for upper-middle class membership (which goes by terms such as lying flat and let it rot) to minimizing engagement with the world in a variety of ways.

The medical professions have naturally sought to frame this voluntary seclusion as a psychiatric disorder, but it is not a disease or disorder, it is a psychological response to an impossible set of familial and social-economic demands in a social order that no longer offers a positive role, socially or economically, for the marginalized and those lacking what it takes to meet the increasing demands of an economy of surplus elites striving for the diminishing pool of jobs that provide both 1) a secure middle-class income and 2) a way of life that doesn’t strip the worker of everything but work.

This is not so much a mystifying disorder as an understanding that seclusion is viewed as the only available response left to social-economic exclusion.

In a hyper-globalized, hyper-financialized developed economy, there are no social or economic roles left for those who cannot enter the coliseum of “highly productive workers” and emerge victorious. Part-time precarious work is all that’s available to them, and it’s poorly paid and earns zero status or respect, so the impoverishment of those for whom this is best they can manage is both physical and psychological.

Trying to live up to the standards of “normal life” extracts more than they have to give in return for an awareness of inadequacy and demands more than they can give in return for the impossibility of meeting expectations in a social order in which ridicule, exclusion and harassment are normalized.

Unable to qualify for social approval and validation–winners must have high social skills and oversized ambitions, be willing to work insanely long hours and pass grueling all-or-nothing exams, then work insanely long hours to prove one’s social merit, marry and have children whose success in a competitive pressure cooker is a heavy responsibility–those who lack these traits either endure a quite realistic sense of the hopelessness of “succeeding” in a competition they are ill-equipped to survive, much less win, or withdraw from the hell of other people (recalling Sartre’s famous line in No Exit: Hell is other people.).

Those who are excluded have said the pain of loneliness is easier to bear than the pain of dealing with other people.

Where working class jobs in factories once offered security, community and a positive identity of being a productive, valued worker, now the physical-labor jobs are viewed as demeaning and those doing the work find their work isn’t validated or respected.

In previous generations, education, vehicles, healthcare and housing were all affordable to anyone with steady work who exhibited basic frugality in service of saving. A great many jobs offered security, community, a positive identity and a ladder of social mobility to lower-middle class stability that then served as a platform for one’s children to climb even higher.

Now working class jobs are characterized by insecurity and precariousness, a threadbare social circle of other workers and neighbors passing through and very little validation of being a contributing member of society.

No wonder so many people devote themselves to curating an artificial digital representation of themselves that they reckon is worthy of recognition and status, and perhaps even admiration and envy. The real world no longer offers much of an avenue for their real selves to receive what every human wants: to be recognized as an individual who contributes to the greater whole to the best of their ability and is thus worthy of self-respect and the respect of others.

I will have more to say about this striving for an artificial substitute for authentic recognition and identity in my next post.

* * *

Tyler Durden

Wed, 05/08/2024 – 16:35