“Nice Narrative” But No: Why One Strategist Thinks Zoltan Pozsar’s “Bretton Woods 3” Is Never Going To Happen

Ever since Zoltan Pozsar started echoing Zero Hedge circa 2010, and in note after feverishly-drafted note, the former NY Fed repo guru has been writing about a coming monetary revolution in which commodity-backed currencies such as the yuan become dominant and gradually displace the world’s reserve currency – the US Dollar – which slowly fades into irrelevancy in a world where commodities are the fulcrum asset and where paper wealth is increasingly meaningless, there have been three reactions: i) those who have no idea what Zoltan is writing about (that would be about 98%), ii) those who agree wholeheartedly and believe that the USD should be dethroned as a reserve currency yesterday, and iii) those who are just a little bit “displeased” with all the attention the strategist (who has correctly called every major crisis and turning point in markets in the past decade) is getting and are starting to lash out at his stream of consciousness.

Rabobank’s Michael Every, himself a geopolitical status quo skeptic yet clearly misaligned with Zoltan as to what happens next (and in reality a believer that the broken system we have now will be the broken system we have for a long, long time to come), is in group three, and following a handful of “subtweet” shots across the Zoltan bow (which have barely registered in the financial media, especially Bloomberg, which Every continuously mocks yet reads religiously) the Rabobank strategist has (bravely) penned the closest thing to a Pozsar rebuttal we have seen.

Is he right, or is he just unhappy with how much attention Pozsar is getting? We leave it to readers to decide, and republish his latest note, “Why “Bretton Woods 3″ Won’t Work” in its entirety below.

Why ‘Bretton Woods 3’ Won’t Work

Nice narrative: but it’s just ‘mercantilism’

Summary

Sanctions on Russia are seen as accelerating a dramatic shift towards a new global commodity-focused ‘Bretton Woods 3’ architecture

However, this is actually a very old economic argument: mercantilism

History, logic, trade data, and economic geography all show the US can do well in that kind of realpolitik environment

By contrast, the opportunity to shift global trade flows away from USD to others is limited: fundamentally, neither CNY nor commodity currencies are set up to rival USD globally

The USD will therefore retain its global role despite the ‘Bretton Woods 3’ hype

Many bad sequels

The world is experiencing dramatic changes in its security, political, economic, and financial architecture. Indeed, alongside war in Ukraine we see headlines about ‘Cold War 2’, ‘Bretton Woods 3’, and even World War 3.

We will not comment on the risks of World War 3, as flagged by Russians such as Karaganov, given it is impossible to trade for.

However, China and Russia are openly trying to build a new world order, which we argued would happen back in 2017: this report focuses on the viability of a global FX architecture remake to a so-called ‘Bretton Woods 3’ (BW3).

We argue that:

BW3 has an appealing narrative, and we agree with a lot of its core arguments. However, it is not a new concept at all, but an old one – mercantilism.

That’s an environment that still suits the US and allies.

As such, we can look at history, logic, trade data, and geoeconomics to see that BW3 will not work as sold.

We may see some USD trade shift to CNY via offset or barter. However, the most this would cover is just 3.3% of global trade, vs. CNY’s current 2.6% share of global FX reserves. The more likely shift is just 1% of global trade.

With much of this being offset, the impact on $6.6trn daily global FX markets would be negligible.

Overall, the USD will retain its global role despite the BW3 claim of a new architecture ahead.

The pitch

Let’s first run through the key arguments made for B3W:

(i) High inflation and supply-chain logjams mean Western central banks and economies can no longer rely on quantitative easing (QE) as a policy crutch: you cannot print commodities. More QE now just means more inflation and currency debasement.

(ii) States instead need control of key commodities and supply chains, including maritime logistics, with military might required to secure them.

(iii) Sanctions on Russia and possible secondary sanctions on others have “weaponised” the USD, euro (EUR), and yen (JPY). Fewer countries will want to hold such reserves if they can be frozen or appropriated, as happened with Russia and Afghanistan. These trends are accelerating a global shift to alternative FX, payment systems, and trading patterns.

(iv) We will see a new commodity- and supply-chain based FX architecture replace the USD-centric system: Russia just called for BRICs countries to create exactly such a new FX system.

(v) Commodity currencies and China’s renminbi (CNY) are seen as major winners in this new order.

A good narrative isn’t enough

Markets like a good narrative.

BW3 has one given: high inflation and commodity prices; central bank impotence; concerns over the imminent withdraw of US QE – and fears over what having to restart it would imply; and talk of geopolitical and geoeconomic realignments and fracturing.

Moreover, BW3 does not require the audience to suspend much disbelief. Relative US political, economic, financial, and military muscle has declined in recent decades.

Even US soft power is fading: and China’s movie box-office has been larger than the US since 2018, dominated by local films. The famous ‘Sunset Boulevard’ line from a fading movie star is, “I Am Big. It’s the Pictures That Got Small.” The US is still big, but others are no longer as relatively small as they were.

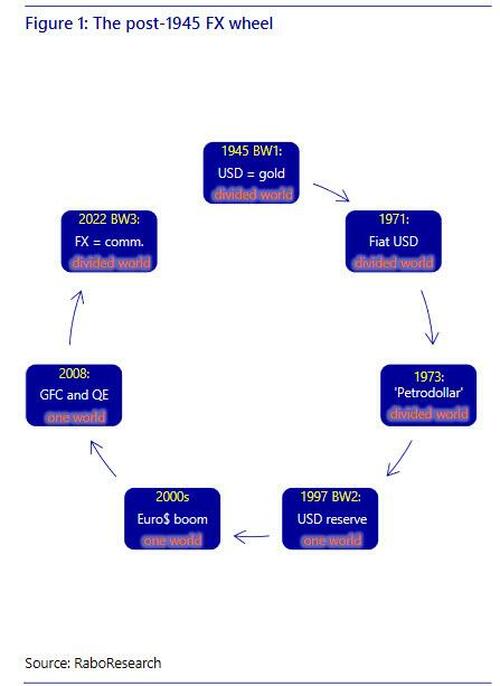

However, BW3 is not new. Indeed, it takes us almost full circle in time and FX structure (Figure1).

In short:

The post-WW2 original Bretton Woods system had USD tied to gold in a divided Cold War world economy with stringent capital controls.

That lasted 26 years before collapsing due to the Triffin Paradox (which we shall return to later) and the shift to fiat USD in the 1970s.

Then we saw evolution to the recycling of so-called ‘petrodollars’ as oil prices surged following the 1973 Yom Kippur War.

The end of the Cold War saw globalisation and higher USD capital flows into emerging markets… and the resulting Mexican (1995) and then Asian Crisis (1997-98)

That led to the de facto BW2 of USD FX reserve hoarding and recycling, as emerging markets opted to run large current account surpluses rather than deficits.

The 2000’s US-steered hyper-globalisation saw a boom in funding in the five-decade old Eurodollar, via both bank and shadow-bank channels.

The Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and subsequent slump in Western growth saw a long-run shift to a reliance on central bank QE to try to stabilise markets and economies.

That ‘new normal’ approach was brought to an end by populist discontent with the inequality it drives, and the fiscal response to Covid: yet Covid also showed reflationary fiscal policies are not possible without national control of commodities and supply chains.

War in Ukraine is pushing us into Cold War 2 – and non-USD ‘reserve currencies’ backed by commodities.

In short, BW3 is not forward, but backwards looking. We have seen many elements of it before. Yet past attempts at building BW3 frameworks created enormous problems!

The post-war Bretton Woods timeframe left excludes it, but one could look to the fragmentation of the global monetary order and trading system in the 1930s, for one key –and worrying— parallel: however, that saw the end of the gold standard, not a move towards one.

Indeed, we have long taken a historical and structural view of markets that leads us to agree on the BW3 view of the ineffectiveness of QE; the geopolitical importance of logistics; the necessity to control supply chains and trade to maintain currency power; and of the ongoing fragmentation of the global economy. We even linked this all to FX structures back in 2015. Furthermore, we agree we are heading not just to Cold War but to global Great Power struggles in which trade and currency will play key roles.

Yet taking this kind of view, it becomes clear that BW3 will still work more in the USD’s favor than for any rival currency being touted.

We will now look at the historical, logical, structural, trade- data, and geoeconomic reasons to briefly summarise Why B3W Won’t Work (WBW3WW).

WBW3WW 1: history

The global economy has seen commodity currency foundations in the past. The most obvious was the gold standard on and off 1815-1971, and in its purest form from 1815-1913. There are many key lessons we can draw from this period for BW3 proponents.

The likes of Argentina saw more FX stability under it that is has since (Figure 2): and Argentina is still a commodity producer today that might be looking at BW3.

However, inflation was only well contained on average by regular deflation (Figure 3). It is unclear that a modern economy would want to see such start-stop price swings.

Moreover, a commodity standard restricts excessive growth of credit by either the government or the banking sector. While a positive case for both can be made, would any economy want to embrace that hairshirt approach?

On the government side, the current vogue is for more, not less state spending in the name of national security: and for more, not less social welfare to narrow income gaps. Without the latter, the gold standard did not stop the many attempted revolutions of 1848 or 1870 in Europe: rather it encouraged them. One could expect the same under BW3.

Russia, which runs a conservative fiscal policy, might be prepared to embrace that approach. However, China cannot. On the private side, China has seen an explosion of debt since 2008: tying itself to an FX commodity standard would mean implosive deflation in Chinese asset prices if new lending was capped. Moreover, China’s total public sector debt, including local governments, is already that of a European state, and the IMF says its augmented fiscal deficit was a staggering -16.5% of GDP in 2021.

Geopolitically, the gold standard was zero-sum. With a (mostly) fixed stock of gold, states either gained the metal through trade, which was also zero-sum, or war. Free trade was tried at British behest, but Europe quickly learned the secret of British success was actually mercantilism and imperialism. It followed suite, with a lag – and so did WW1 (Figure 5). Indeed, ‘Debt: The First 5,000 Years’ (Graeber, 2011) echoes Polanyi (1944) in arguing past historical periods of exogenous money, such as gold, saw more war

compared to endogenous, fiat/debt-based periods of expansion.

Of course, when debt-based expansions end similar problems can arise, as we see today: yet embracing a global commodity currency standard would guarantee that outcome from the outset.

WBW3WW 2: logic

The four logical functions a global FX reserve currency must meet are: (i) store of value; (ii) method of accounting; (iii) means of exchange; and (iv) overcoming the Triffin Paradox. All of these still favor USD over any rivals.

Store of value

Commodity currencies are either pegged to the USD, in which commodities are priced, or are highly volatile (Figure 6). Unless global commodities are now going to permanently lose that volatility, and volatility is actually increasing in many of them, then commodity currencies will not lose theirs either.

No rival global currencies offer the trust of US markets. Yes, USD (EUR, JPY, etc.) are now “weaponised” for Afghanistan, Russia, Belarus, and anyone who supports the invasion of Ukraine. However, CNY is highly politicized, as is RUB, and Chinese markets have seen net capital outflows since the start of the Ukraine War. Do any potential BW3 currencies inspire broad global trust, or just in pockets?

High US inflation hardly backs the USD. However, the Fed is flagging rate hikes of as much as 325bp this year and quantitative tightening (QT). That backdrop will support USD: and that is true if that level of rates can be sustained, or if it can’t, and the US (and world) economy falls into recession – taking commodity prices with it. Only if the US re-embraces QE despite high inflation would the USD’s store of value be undermined.

We agree that military power ultimately underpins global reserve currencies. On that front, while overstretched, the US still holds primacy, and its allies in Europe, Australia, and Japan are rearming rapidly. By contrast, Russia’s martial prowess has been called into question in Ukraine, and China’s remains entirely untested, despite the incredible growth rate of its armed forces.

Method of accounting

No other global currencies offer the scale of US markets or its ‘network effect’. Try to talk about trends in global GDP without using USD as the common denominator. In a reflexive logic, the more people who use a currency, the more the currency is used.

This is particularly the case in terms of Eurodollars (offshore USD borrowing). The sheer scale –hence power– of Eurodollar debt means setting up an alternative is a daunting task: even China had $2.7trn of FX debt as of the end of Q4 2021.

Indeed, if one presumes USD will be pushed aside, one is logically arguing a lot of Eurodollar debt will default, as few will be able to earn enough USD to repay it. That would mean global market chaos.

Means of exchange

The USD is welcomed globally, and its high liquidity means low transaction costs. The same is not true for any other potential alternative currencies.

Indeed, China lacks an open capital account, which means CNY is not free-moving or freely traded. This is an economic policy choice on China’s part which hugely limits CNY’s global attractiveness.

Triffin Paradox

The Triffin Paradox is that global demand for a reserve currency forces the country that owns it to run trade deficits. For fiat USD that also means offshoring industry (i.e., via foreign net exports to the US) and, as we now see, rising domestic inequality. There is growing pushback against this within the US, but no idea of how to maintain USD’s reserve status while doing so.

Any BW3 currency trying to push USD aside would have to be willing to run large trade deficits too. However, if commodity prices are high, major commodity producers run trade surpluses, stopping the spread of their currency; and if commodity prices collapse, their currency does too, again limiting its global attractiveness.

China also runs a large merchandise trade surplus (even if it also runs a huge commodities deficit) in order to support industrial employment, as well as to ensure the stability of CNY via the balance of payments. Combined with capital controls, this further limits any global reserve role that the currency could ever hope to play.

How does one earn CNY? How do CNY get into the global system within BW3?

WBW3WW 3: structure

Fundamentally, BW3 does not work because of the structure of the global economy. The essential nature of commodities has been laid bare by the Ukraine War, but total global trade in them is still far smaller than other goods combined (Figure 7). That is a very low ceiling, or narrow base, to build a new world order on.

Perhaps if all commodity exporters were united it might be possible – but they aren’t.

Indeed, only a few major food exporters are pro-BW3 (Table 1). One can take out the Western producers: Australia, Canada, the EU, New Zealand, and the US.

In terms of energy, there are again major Western producers –Australia, Canada, and the US– but the majority are located in the Middle East. The US is the traditional hegemon there too. True, this situation may be changing as the US tries to pivot to Asia and is dragged back to Europe by Russia – but it is a huge geopolitical gap for China to fill, even presuming the US doesn’t pivot back.

Moreover, global oil markets need a base currency that is: liquid, which CNY is not; freely tradable, which CNY is not; and stable, which CNY only is because it does not meet the other two criteria, and because it is soft pegged to the USD!

Even a move to oil priced in a basket of currencies is hugely complex to maintain across all OPEC partners, which is why it has not happened yet. Hence energy producers are seen as ‘floating’ at best but are hardly set to rush to switch the USD for CNY (Table 2).

In terms of mineral exporters, there are a large number of floating countries, and the same general cluster in the pro-West and pro-BW3 camps.

The simple message is that BW3 has a significant tranche of global commodities behind it, but mainly because of Russia; the West has the same, but because of a broader range of resource-rich economies; and most of the world’s producers are looking on at the prospect of a global bifurcation with extreme discomfort.

In short, BW3 does not yet have buy-in even from the majority of economies that are supposedly the primary beneficiaries of it.

WBW3WW 4: more structure

As just alluded to on oil, we have another issue: which currency will dominate BW3 trading? It’s one thing to say, “commodity currencies.” It’s another to explain how the BW3 would function if BRL, ARS, AUD, RUB, IRR, etc., were all commodity pricing currencies simultaneously. Who would clear this? At what exchange rate? In what system?

Until that is resolved, the USD needs to remain the currency commodities are priced in, even if we see some offsetting BW3 transactions in local FX.

Indeed, the proto-BW3 is attempting to keep the current global architecture while trying to cut some USD out of some trades, or to insert another currency where they were previously absent. To give three key examples:

Saudi-China CNY oil sales: Saudi Arabia may export some oil to China and be paid in CNY for the first time. It exported $56bn of energy to it in 2019 – but that is a fraction of the $2.6 trillion traded global oil market.

Because the Saudis’ own currency is pegged to USD, it would open itself up to FX volatility using CNY. As such, Saudi would price oil in USD and allow (some) payment in CNY; then the Saudis would sell the CNY back for USD.

There are limits to what Saudi Arabia would sell in CNY, however, to avoid accumulating CNY of no use to them unless everyone else makes the same shift.

Russia-India INR trade: Floated trade between Russia and India to avoid USD will also be priced in USD and transacted in INR. A bank account will be opened in India for Russia, and as Russian commodities (and weapons) arrive in India, INR will be credited to it: as Russia buys goods from India, the account will be debited.

This is de facto bilateral barter, technically in INR, and leaves Russia with either the need to buy more than it needs from India, or to accumulate INR claims it cannot usefully transfer elsewhere.

Europe-Russia RUB trade: Russia demanded to be paid in RUB for its gas, and perhaps all commodities, and Europe refused to do so. Yet a face-saving solution was found. Europe still pays for Russian gas in EUR or USD, but Russia insists on Gazprombank selling them for RUB to a Russian entity before both are then remitted back to Russia.

Meanwhile, Europe appears intent on – slowly – decoupling from Russian energy completely.

It should be clear that a BW3 anchor FX/clearing currency would have to be found.

Even though China is huge commodity importer, not exporter, which runs counter to the whole BW3 concept, CNY is the obvious candidate as a BW3 anchor: only China has the economic scale.

As already shown, CNY does not meet the criteria to be a global reserve currency because of its closed capital account and trade surpluses. However, for the BW3 commodity producers that China runs a deficit with, CNY may be able to play a larger role. (Figure 8.)

Yet because CNY is still not going to be a true global alternative to USD for structural reasons, there are still rigid limits on how much bilateral China-BW3 trade we might actually see shift, as we shall now show.

WBW3WW 5: trade data

The numbers don’t add up for BW3 and CNY – at least not as a global game-changer.

Total global exports and imports were $38trn in 2019 (Figure 10) to remove Covid/post-Covid distortions. The US accounted for $4.2trn; Canada, the UK, Australia, and Japan –all 5-Eyes geopolitical allies, or under the US defence umbrella– $4.0trn; the Eurozone $5.2trn internally and another $4.0trn externally; China $4.6trn; and the rest of the world $16.2trn, most of it in USD. (NB the data are only available in USD!)

In summary, China accounted for 12% of global trade vs. just 2.6% of central bank reserves at end of 2021 (Figure 11). On the surface, that appears a very bullish argument for the currency, BW3 or not – and BW3 argues it will rise.

However, we need to dive into that $4.6trn/12% data to show why CNY is not doing better, and likely won’t do much better even under a proposed BW3.

(Figure 12 shows China’s trade breakdown by region and separates Russia from the continent of Europe for obvious reasons.)

First, China’s trade with Hong Kong ($561bn) is counted as external. We colour it red to show it is part of the national economy. China could switch that to CNY but would undermine the role of Hong Kong and the HKD’s USD peg.

Then we have Russia ($111bn); the Middle East ($263bn); Africa ($208bn); Asia excluding Japan, India, and South Korea ($728bn); and Latin America ($315bn) adding a further total of $1.6trn. All are shown in shades of orange to indicate they are open to doing trade in CNY.

However, more than half of total trade ex. Hong Kong is with North America, Europe, Oceania, or parts of Asia that for geopolitical reasons will not trade in CNY. Moreover, China’s trade patterns (Figure 13) show how much it relies on surpluses with North America and Europe: the risk is that the more China backs BW3, the less the West trades with it, undermining its total trade surplus.

In short, China’s maximum CNY global trade share is 4.3% vs. its current 2.6% share of CNY reserves globally.

The primary targets for a major USD > CNY switch are in Asia ex. Japan , India, and South Korea (Figure 13). However, ‘orange’ countries might only shift some trade to CNY, not all of it: the trade logic says that will be the case.

China imported $211bn of goods from Asia* in 2019, half primary goods/resources, where we presume it could be the BW3 anchor, half manufactures (Figure 14). It exported $517bn of low, medium, and high-tech items as part of electronics supply chains.

This left a large trade surplus for China. If bilateral trade was all in CNY, Asia* would need Chinese FDI or loans to cover its trade deficit, with no means of net earning CNY. Moreover, many of the electronics goods it imported from China are re-exported to Western markets, earning USD.

As such, the maximum Asian* countries would want to shift to CNY would equal their China exports, as an offset to their imports from China (the red area in Figure 14). So, the total shift in trade is not imports and exports ($728bn), but Asia’s* exports to China ($211bn) doubled, which is $422bn.

Yet the number is likely even lower given the complexity of managing balanced CNY trade in so many categories of products. We could perhaps see the total of Asia’s commodity exports to China shift to CNY, so only $120bn. As such, total CNY trade might only be $240bn from a total of $728bn. And presumably those commodities would still be priced in USD – at least until the Middle East, from which Asia* buys energy, changes its currency peg.

Similarly, China’s trade with the Middle East saw it import $146bn of mainly primary goods/resources, while exporting $116bn of a broad range of goods (Figure 16).

China obviously wants to buy all its commodities in CNY. However, as already noted, the Middle East, with currencies mainly pegged to USD, would only consider switching trade to CNY to the total of their import bill from China, which is less than that total.

In short, $116bn of Middle East commodity sales could shift to CNY and be doubled with $116bn of CNY flowing back in the other direction for consumer goods. That is the maximum CNY shift unless China sells a lot more to the region, which would arguably need to be military equipment. The geopolitical risks there should be clear!

If oil and gas are still priced in USD, this would be de facto barter or countertrade avoiding USD more than real trade in CNY.

Looking at Latin America (Figure 17), the region exported $149bn of commodities to China, and China sold it $151bn of goods of all kinds. Here we see a genuine argument for more CNY trade compared to the total bilateral trade being done.

The picture is similar for Africa (Figure 18), where total exports to China were $95bn, of which $85bn were commodities, while China sold $113bn of goods to it.

We should also add Russia (Figure 19), where Chinese exported $53bn and imported $57bn, with Russia running a slight trade surplus. For obvious geopolitical reasons, Russia is rapidly embracing CNY – but major Chinese firms from SOEs to Huawei are still wary of US and EU sanctions so far.

Using this methodological approach for each region/economy China trades with, we can summarise the total global CNY shift we expect to see (Figure 20).

The total theoretical CNY shift is if all trade moves to it under BW3. However, only some countries would and not all countries will do all trade in it: grey areas indicate where they will not.

The major CNY shift (in light orange) is if all potential pro-BW3 countries maximize their CNY trade at the level of their total imports or exports, whichever is lower.

The likely CNY shift assumes a lower move to CNY with an assumed coefficient driven by geopolitics.

In Russia’s case we assume it is 0.8 (i.e., 80% of maximum shifts to CNY). For the Middle East, we assume 0.25 because of USD pegs; for Africa, 0.30 given geopolitical competition for its commodity exports from Europe, Japan, the US, and India; and for Asia* and Latin America 0.25 because of economic competition and/or ties to Japan or the US.

The results are hardly a paradigmatic shift away from USD:

The major CNY trade shift is worth $1,254bn, equal to 3.3% of global trade vs. a current CNY global reserve equal to 2.6% of the global total. As such, CNY holdings would rise by around a third in Africa, Latin America, the Middle East, and Russia – but nowhere else. (Figure 21.)

The likely CNY trade shift is worth $381bn, equal to 1% of global trade. That is lower than the current holdings of CNY reserves: while some economies would add more, Western economies may hold less. (Figure 21.)

In terms of FX trading, the major shift is only worth $4.8bn per working day, a drop in the ocean for the $6.6trn global FX markets, and much of that would be offset trading, not selling USD for CNY. In the more likely case, it is only $1.5bn a day, which would hardly be noticed.

In short, BW3 is not looking like a global alternative to USD – just a cluster of Chinese hub-and-spokes offset/barter trades trying to avoid USD as middleman.

WBW3WW 6: geoeconomics

BW3’s prospects would be boosted if CNY was adopted by third parties globally: yet we have already explained why this is structurally very hard to achieve.

Two countries that both run trade surpluses with China, e.g., Brazil and Russia, could decide to use CNY to settle some bilateral trade. However, given CNY would remain structurally locked out of the USD’s broader global role, this could arguably best occur within the specific industries that earn CNY: how much intra-commodity industry Brazil–Russia trade do we see? Not much at all.

This is economic geography at work – and against BW3.

Global trade-flows mean even if more commodity producers were on board with BW3 it would count for little because BW3 does not replicate the structure of commodity producers, goods manufacturers, and final consumer markets – which are mainly in the West.

Commodity producers can try to force the West to take their currency, like Russia, via economic coercion. Yet countries running large trade surpluses don’t allow others to earn that currency to pay in it!

Moreover, the West can walk away – as it is pledging to do from Russian energy. Unless every commodity producer backs BW3, there are alternatives – and/or technological innovation to reduce commodity intensity. And, to reiterate, if all key commodity producers walked away from the West, they would lose those markets for their commodities.

The only way BW3 could avoid this problem would be if the global economy fragments into multiple value chains. The West still has key resources, technology, allies, a strong military, and could even onshore production if needed: could BW3 commodity producers (and China as importer) replicate or sustain value chains without Western technology and Western end consumers? Looking back, some BW3 countries tried that during the last Cold War – and import substitution did not work well for them (Figure

22).

Moreover, look at the terrible demography in Russia and China, and their structural economic problems. Could either afford to walk away into a more isolated, combative realpolitik BW3?

It seems highly unlikely Russian autarchy work this time given repeated failures over the course of history. How long until it can replace its foreign-built capital stock, foreign-designed cars, trucks, and planes, or high-tech goods?

China could fill that BW3 technology gap: yet if so, it would lose Western markets. We would see geopolitical fragmentation – not horizontally, as BW3 commodity producers replace the West, but with parallel value chains from commodity producers to China and the West.

Yet look back at Figure 13 and imagine what the loss of a net $430bn in EUR and USD net trade inflows would do for China’s economic and FX stability. That is more than China can hope to offset with lower use of USD under BW3.

And what would decoupling mean for its commodity demand, which is where it is supposed to be the BW3 anchor? And let’s not forget China already has economic problems that call into question how long it will remain a giant commodity consumer (i.e., iron ore).

Mapping out the problem

To make these economic-geography points in another way, we created 3-D BW3 trade maps (Figures 23, 24) that show intra-BW3 trade by region, excluding India, Japan, and South Korea and China; and with China and the US.

The conclusion should be immediately obvious: intra-BW3 trade excluding China is only a fraction of that between each of those regions and China,… or with North America – which can be seen is still a hugely important trade partner for most of them.

In short, CNY will not be adopted by third parties either within BW3 or outside it.

WBW3WW: conclusion

Alongside dramatic world events ‘Bretton Woods 3’ has an appealing market narrative. Indeed, we agree with a lot of its core arguments, depressing as they are.

However, it is not new. It is old. And in not looking back enough, it fails to look forward sufficiently.

To argue that we are going to see shifts to Cold War and global Great Power struggles, and a world in which commodities, logistics, and the military all play key roles alongside finance and currency, and with a geopolitical need to run large trade surpluses, is to argue for an ancient economic philosophy: mercantilism.

Modern economists may have forgotten the true meaning of that term, but it reigned as long as commodity currencies did – and it implies a highly realpolitik global environment. To be fair, BW3 implies the same without naming it directly.

Yet is that backdrop negative for USD and positive for BW3? No.

A mercantilist realpolitik environment is one in which the requisite set of resources and diverse sources of power, after some policy shifts(!), still rest more with the US and its allies and their military, soft power, and financial power, than with a cluster of commodity-producing states (and one commodity importer).

That is especially true if that cluster want to create a parallel economic and financial structure from disparate net exporter polities, who do not trade horizontally together to any great degree, and while also still exporting to the rival West!

As such, BW3 will not work, and USD will retain its leading global role – albeit perhaps with more sticks and fewer carrots.

If we were to see fewer USD circulating internationally via trade, servicing Eurodollar debt will just get harder – and that will keep a structural bid behind USD. By contrast, borrowing in CNY will still be unattractive for almost every economy given China’s persistent trade surpluses and capital controls.

As such, on BW3 all we will see at best, is a marginal increase in the ‘offsetting’ use of CNY ahead – and more rapid global decoupling, likely to its ultimate detriment.

Tyler Durden

Wed, 04/13/2022 – 19:00