Prosecuting Trump In The Shadow Of Hillary’s Emails

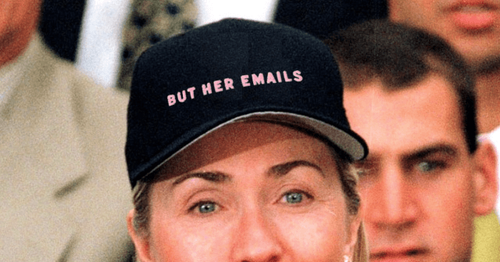

Hillary Clinton recently hawked a line of hats with a mocking logo — “But her emails.” The taunt was directed at Donald Trump, who faces a real possibility of a criminal charge after the FBI’s search of his Mar-a-Lago residence.

While Clinton considers her prior conduct a subject of mirth, the FBI’s handling of her case will cast a long shadow over any potential prosecution of the former president, including the recent focus on an obstruction charge. There likely would be an assortment of “but her emails” objections to a charge that could have been made as readily against Clinton or her associates.

The appointment of a special master to examine materials seized in the Trump investigation has occupied much of the attention in the past week. Trump’s legal team’s belated request for a special master could help bring greater clarity to the raid’s scope and seizures. Yet it will not likely alter the trajectory of the case, which the Department of Justice (DOJ) has repeatedly stressed is an “active criminal investigation.”

What is notable is the government’s obvious effort to focus public attention on obstruction as a potential crime. Emphasizing obstruction, instead of the improper retention of classified material, could be seen as a way to navigate a political minefield to get to a prosecution. The reason, once again, is Hillary Clinton, who remains a complicating factor in Attorney General Merrick Garland showing the public that this is not about pursuing Trump but enforcing the law.

In its filings in the last two weeks, the most worrisome line for Trump came in the DOJ’s 36-page opposition to a special master’s appointment when it declared that “obstructive conduct occurred” at Mar-a-Lago in the months leading up to the Aug. 8 search. The DOJ also said it “has developed evidence that government records were likely concealed and removed from the Storage Room and that efforts were likely taken to obstruct the government’s investigation.”

Those types of statements never bode well for a target, since they reflect a certain commitment to the prosecutorial path.

The value of shifting toward an obstruction case is that it would reduce the complications of any Trump claims on declassification or executive privilege to remove documents while he remained president. (The three cited statutes do not require classified status for a crime but two deal with the unlawful possession or handling of defense or sensitive information.) Trump has not fully explained how he allegedly declassified all of this material. Under Section 1519, the government can prosecute someone who “knowingly conceals any document with the intent to obstruct” their investigation.

The filings do not indicate that the government has evidence of knowing concealment by Trump, but it cited various representations made by lawyers on his behalf.

Trump might be familiar with such cases because he pardoned Jesse Benton in the final days of his administration. Benton, who managed Ron Paul’s 2012 presidential campaign, was convicted of violating Section 1519 by concealing campaign payments from the Federal Election Commission. Ironically, Trump signed that pardon as his staff was preparing to leave the White House, including having these boxes packed for transport to Mar-a-Lago.

While the released evidence would clearly support a charge of obstruction, it is unclear what acts were knowingly taken and by whom.

A criminal charge of obstruction against Trump would offer certain political benefits for Garland. As previously discussed, the government has routinely elected not to prosecute high-ranking officials for improperly removing classified material or has sought mere misdemeanor charges in the most egregious cases.

Prosecuting Trump for a misdemeanor for possessing or removing classified documents would seem gratuitous, while prosecuting him for a felony would raise questions of biased or selective prosecution. After all, in 2016, Hillary Clinton had not just 113 documents containing classified material but some documents “classified at the Top Secret/Special Access Program level” on her private email servers. (In Trump’s case, the government allegedly found roughly 100 documents in the Mar-a-Lago raid in addition to roughly 150 handled over by the Trump team under an earlier subpoena.)

Clinton’s documents were even more vulnerable to being compromised via her unclassified email account and, according to the FBI, “hostile actors gained access” to some of the information. Yet she was never subjected to a raid, let alone a charge.

Yet, while less glaring as a contradiction than the charges on the possession or handling of classified information, an obstruction charge would allow up to a 20-year sentence and could be brought with misdemeanor charges on the mishandling or retention of classified information.

Thus, an obstruction charge against Trump would be prosecuted in the shadow of Hillary Clinton’s case. In addition to the transfer of top-secret and other classified documents to her private server, Clinton and her staff did not fully cooperate with investigators. During the investigations of her conduct, some of us marveled at the temerity of the Clinton staff in refusing to turn over her laptop and other evidence to State Department and DOJ investigators. The FBI had to cut deals with her aides to secure their cooperation.

Later, more classified material was found on the laptop of former congressman Anthony Weiner (D-N.Y.), who was married to top Clinton aide Huma Abedin — 49,000 emails potentially relevant to the Clinton investigation.

After Congress sought these emails, Clinton’s staff unilaterally destroyed thousands of emails with BleachBit. Clinton was aware that Congress and the State Department were seeking the emails in 2014. Her lawyers turned over about 30,000 work-related emails to the State Department and deleted 33,000 others while insisting they unilaterally deemed them “personal.”

Garland may be able to make a case against Trump and show that it is indeed distinguishable from the Clinton case and others. What has been alleged is undeniably serious, including the alleged failure to comply with an earlier subpoena and false statements. However, Garland must address the legitimate concerns of millions of Americans that the same office involved in past Trump investigations — with documented instances of false or misleading statements — is leading this new effort. There also is the great concern over the Biden administration charging a prior and possibly future political opponent.

Any criminal case should be based not only on unassailable legal theories and facts but on clear consistency with past cases. That case will turn on still undisclosed evidence of what was known about the contents of the boxes found at Mar-a-Lago and how the documents were handled after the Trump team learned of the FBI’s investigation.

With Hillary Clinton selling “But Her Emails” hats at $30 a pop, Merrick Garland will have to explain the prospect of one politician going to jail while the other goes retail.

Tyler Durden

Sun, 09/04/2022 – 14:30