Fed Balance Sheet Shrinkage Kicks Into High Gear In September

The Fed began shrinking its balance sheet in June (at a pace which for various reasons many have found to be too slow but in reality is just as fast as had been expected, as we will explain tomorrow) and plans to double the pace at which it reduces its securities portfolio in September. And while there are ample reserves and liquidity for now, many prominent Wall Street strategists have warned that the Fed will have no choice but to end its QT much earlier than expected.

Some more details on the recent trajectory of QT, courtesy of SocGen’s Stephen Gallagher:

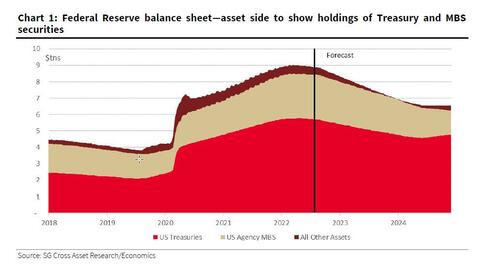

Fed to roll off as much as $95bn per month from September. The Fed allowed $30bn of Treasury and $17.5bn of mortgage-backed holdings to mature in June. In September, the Fed will double that amount, increasing the caps or run-off amounts to $60bn per month for Treasuries and $35bn per month for mortgage-backed securities. The impact on yields, if any, has been overshadowed by macroeconomic concerns and volatile rate-strategy expectations. For now, the primary channel for monetary policy remains the fed funds rate.

2019 taught us that the Fed needs to maintain a flexible approach to its balance sheet policy. The size and pace of shrinkage should be tied to both economic performance and to controlling short-term rates that are intricately tied to its fed funds rate policy, such as repo rates for secured overnight lending.

Fed balance sheet liquidity for financial institutions at $5.5tn. In 2017-2019, the Fed’s balance sheet run-off shrank bank reserves held at the Fed from a peak of $2.36tn to $1.39tn in September 2019 when repo markets turned disorderly and broke out of the Fed’s desired rate corridor. Today, the Fed has over $5.5tn in reserves including $3.3tn of bank reserves held at the Fed and $2.2tn in the Fed’s overnight reverse repo programme that was created during the most recent expansion of the Fed’s balance sheet.

Consensus foresees slightly more than $2tn in balance sheet reduction: the Fed is expected to sustain its $60bn per month reduction of Treasury holdings until the end of 2023. After that, the pace of reduction may slow and cease by spring 2024. The Fed may independently sustain reductions of its MBS portfolio throughout 2024. Eventually, the Fed will need to buy Treasuries again to offset the reduction: the $64 trillion question is when.

The bank reserves and reverse repo program together need to shrink by more than $2tn in order to achieve total balance sheet reduction of $2tn, reduction which would lift the effective fed funds rate back toward the Fed’s interest on reserves (IOR). If it continued to rise far above the IOR, the Fed’s standing repo facility would be activated and balance sheet reduction might be reversed, as in 2019. The sensitivity of rates to the volume of reserves in the system is lower (flatter curve) than in the 2017-19 episode. Two factors likely account for this: the substantially larger size of the balance sheet and the introduction of the reverse repo platform.

Items to monitor

Economic performance: this is linked more to rates but also the total size of the balance sheet. Weaker economic performance would first bring a halt to rate hikes, but then could slow or end balance sheet reduction.

Overnight rates moving outside the Fed’s corridor: the Fed wants to exert strong control over rates through its setting of the interest on reserves (IOR), the fed feds rate and repo rates. Abrupt changes could prompt adjustments in the IOR relative to the fed funds rate target and possible changes to the balance sheet policy if market rates become more volatile.

Relative holdings and specific liquidity issues: there is a concern about illiquidity in the Treasury and mortgage markets that could prompt changes in the Fed’s balance sheet strategy. Specifically, the Fed has raised the possibility of outright selling of mortgage-backed securities. The reason is that prepayments or maturities of these securities are largely determined by the borrower. Reducing its holdings by allowing maturities or pre-paid debt without rolling over might be slower than desired. Additionally, over time the Fed wants its portfolio of securities to be primarily Treasury holdings. We do not expect changes in its current roll-off strategy but are monitoring this. In 2024, we expect the Fed to initially slow the reduction of its Treasury holdings before halting the reductions. Eventually, the Fed should buy Treasury securities to offset reductions of the MBS holdings.

Lessons from earlier QT

From January 2018 until September 2019, the Fed reduced its total assets by just $600BN from $4.4tn to $3.8tn, at which point the repo market broke. As QT progressed, upward pressure on overnight rates moved EFF and SOFR above their floors. By September 2019, reserves amounted to $1.4tn. Demand for ON RRP borrowing was near zero: the upward spike in SOFR demonstrated reserves were clearly not ample at this level. The Fed reversed course and expanded its balance sheet by lending in the repo market to set a ceiling on rates, and launched NOT QE, which was of course, QE. The floor system was back to a corridor.

The vertical lines in charts 2 & 3 show the current level of reserves + ON RRP borrowing and SocGen’s forecast of the level at the end of 2023 if the Fed implements its plans to draw down the SOMA. The level of reserves + ON RRP also depends on the movements of the other large Fed liabilities (currency in circulation and the Treasury general account). As the Fed nears its terminal target rate, expect the ratio of reserves to ON RRP to rise. Can the Fed implement its proposed balance sheet reduction while maintaining enough reserves to control overnight rates? The answer is probably not for reasons explained by BofA’s Marc Cabana.

The level of reserves + ON RRP at the end of 2023 is projected to be $3.7tn. This is well above the levels at which rates started to become unmoored in 2019 (around $1.7tn). If the demand curve for overnight lending remains the same as in 2019, the Fed should have no problem controlling its target rates while reducing its balance sheet until 2023. Then, as the SOMA drawdown continues into 2024 and 2025, reserves will draw closer to the problematic 2019 levels.

However, in a world of “all else equal” nothing ever is, and we know the demand curve for overnight lending is not stable over time, and it may and will shift for many reasons. For example, more restrictive liquidity and capital regulations can drive demand higher. The Fed regularly surveys banks and puts a lot of work into estimating the necessary level of reserves. Nevertheless, the Fed did not foresee that it would have to reverse QT in 2019 at a level of reserves far above pre-2008 levels. If demand for reserves going forward is higher than in 2019, the Fed will have to halt QT sooner than expected to maintain control of overnight rates. More on this premature end to QE in a subsequent post.

Tyler Durden

Wed, 08/24/2022 – 09:45