Cold War Lessons For US-China Today

By Jordan Schneider and Irene Zhang of ChinaTalk

How did the Cold War affect US diplomacy and its actions abroad? And what lessons about gently coaxing Gorbachev back into the bosom of the international community need to be relearned?

Hal Brands (@HalBrands), professor at the Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies, is the author of Twilight Struggle: What the Cold War Teaches Us about Great-Power Rivalry Today. Along with co-host Emily Jin (@ew_jin) of the Center for a New American Security (CNAS), we discussed:

How the US capitalized on Soviet heavy-handedness in the developing world

The US’s never-ending cycles of self-confidence and self-doubt

Today’s Sinologists versus Cold War Sovietologists

Why the only person who can stop the war in Ukraine is the one who started it

Applied history, and why the Cold War?

Jordan Schneider: Applied history, what is it and why isn’t it more of a thing?

Hal Brands: Applied history is basically just a fancy way of saying that you study history not for its own sake, even though that’s important, but for what it can teach you about how to handle the problems of today and tomorrow.

This is actually the oldest possible use of history; there’s literally nothing new about it. If you go back and read Thucydides, he doesn’t use the term applied history, but he says that his History of the Peloponnesian War was meant to serve as a guide to statecraft and subsequent eras. In fact, I would say that this is why most people read history. It’s mostly professional historians who think that history should be studied for its own sake.

The challenge, I think, is that within the historical profession, there has long been a concern that doing history with an eye to shaping policy risks is diluting or compromising the scholarly objectivity on which good history is supposed to depend.

I think that that’s a fair point, and there are good examples of people who have allowed the quest for influence or whatnot to distort their historical work. But I think there are ways of balancing that challenge.

In fact, I would say that it’s hard for me to justify the doing of history if you’re not trying to make a point that’s relevant today.

Jordan Schneider: Why spend part of our marginal 10 hours of reading time a week on the Cold War?

Hal Brands: Part of it is that we all know something about the Cold War and we all probably have an image of the Cold War in our heads. It occurred within the living memory of a lot of US policymakers right now. I guarantee Joe Biden has some understanding of the Cold War, and that understanding probably plays some role in his policy decisions on issues from Afghanistan to Ukraine.

One of the arguments I’m making in the book is that the Cold War actually isn’t that exceptional. There are aspects of the Cold War that are exceptional: it’s the only great power rivalry that played out in the shadow of nuclear weapons, to give you one example. But then, it’s part of this much longer phenomenon of protracted great-power competition that goes back to the beginning of recorded history. So it ought to be able to teach us something interesting about that larger phenomenon at a time when it’s coming back to life in the form of the US’ relationships with China and Russia today.

American Exceptionalism and the Pitfalls of Ideology

Jordan Schneider: The day after Biden’s State of the Union, I was thinking: Biden is saying this stuff about how we’re the best country and we can do anything, and I’m like, oh, I really hope so. To what extent did folks back then buy this? Throughout the entirety of the Cold War, how did that sine wave flow in and out over time?

Hal Brands: I don’t think they bought it any more than they buy it today.

There was never an uncritical belief that the United States could do everything and that its influence was entirely benevolent and benign.

It’s quite often the opposite. The United States went through periods of intense self-doubt during the Cold War, and even times when the country was tearing itself apart over things that it had done overseas — just look at the domestic bombings, some of which were related to the blowback over the Vietnam War throughout much of the 1970s.

There are big debates in the United States over whether we should have NATO anymore, and whether we should still have alliance commitments around the globe. We go through these cycles of self-confidence, and then a lack of self-confidence.

This is normal; when threats are running high and we’re feeling good about ourselves, we embrace a very expansive conception of what we think we can achieve in the world. Then, when something goes wrong, like the Vietnam War, we decide that we are really unable to accomplish anything. It typically takes some sort of advance by the bad guys to shake us out of that. That’s a normal part of American history. We see that cycle repeatedly during the Cold War.

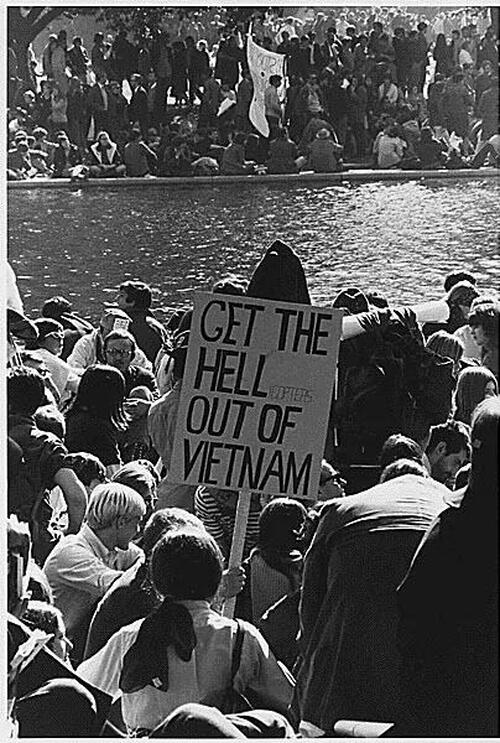

Vietnam War protest in Washington, D.C., October 21, 1967.

Emily Jin: Fusing geopolitics with values or ideology, while powerful for holding a nation together, is also possibly going to lead to bad policies. How would you design an approach that actually leaves room for both unity and clear-headedness, that could detect bad policies?

Hal Brands: You probably can’t. If you want a political consensus strong enough to sustain American participation in a long-term competition, you have to tap into that ideological fervor that is very deeply rooted in the American psyche.

This is what Harry Truman understood. It’s what Ronald Reagan understood. It’s what all of the policymakers who really spoke to Americans best about the Cold War and what it represented understood, and they weren’t entirely wrong about that. I think that they were right in thinking that what was ultimately at stake in the Cold War was a contest between two fundamentally different visions about how people in societies should be organized.

But it’s like any pep talk: it’s easy to take it a little bit too far and hard to downshift into a lower gear at a particular time. The way that I try to frame this is that any political consensus that was strong enough to inspire the sort of investments that the United States was going to need to win the Cold War was also going to be strong enough that people like Joe McCarthy could abuse it, or strong enough to lend itself to red-baiting.

Jordan Schneider: This seems to be the dilemma: on the one hand, you get the Vietnam War, driven by this ideological fear that, that if we screw this up, the whole world’s going to know that we’re a paper tiger and America doesn’t stand for anything.

And on the other hand, you get these conversations that you bring to light very well through archival work, where leaders basically say that these are trade-offs that that we have to make because there’s a bigger bad behind all of this, and we’ve got to make sure that we’re doing everything we possibly can so that Marxist-Leninism doesn’t take over the planet.

Hal Brands: Jeane Kirkpatrick had a saying in the early eighties: there are degrees of evil in the world. So the alternative to working with Efrain Rios Montt in Guatemala might be something even worse than that. There’s a certain amount of truth in that, obviously.

The challenge, of course, is that there is always a point at which means can corrupt ends, right?

There’s always a point at which the way you pursue a certain goal can undermine the worthiness of the goal itself.

I think it’s a fair question to ask whether the United States occasionally got itself in positions where its own conduct was so bad, or had backed people whose conduct was so bad, that it undermined the larger moral cause it was trying to support.

President John F. Kennedy hosts Suharto in Washington, D.C., 1961. (AP)

Jordan Schneider: On your degrees-of-evil scale, I’m not sure how much further Suharto can fall down. And it’s not just him: there were plenty of others, and one wonders if less death and awfulness would have befallen these countries if their left-leaning alternatives had stayed in power. I grant you that these were difficult decisions, but I do think in retrospect that there were plenty of these battles which the US could have just decided not to fight.

Hal Brands: It’s important that we not overstate how much control the United States had in some of these situations. My friend Ray Takeyh has shown pretty conclusively that the United States had a nontrivial, but perhaps non-decisive, role in the 1953 coup in Iran. The United States was deeply involved in de-stabilizing Salvador Allende’s government and Chile in the early 1970s, but as far as we can tell was not deeply directly involved in the coup that actually overthrew him in September 1973 (although we certainly supported it after the fact).

So in many cases, the choice wasn’t: should you go make people do these terrible things in the Third World or not? It was: given the trend of events, should you support actors who are doing morally questionable things, or should you refrain entirely?

Parallels Between Sovietology and Pekingnology

Jordan Schneider: The current job market for China analysts, as Emily and I can attest to, is shockingly thin, and it breaks my heart when listeners reach out to me for career advice. The supply exceeds demand and salaries are low. The market is growing at 5 or 10% a year, not at the pace that it seemed like in the 40s and 50s when the US really spun up a remarkable effort to bone up on all things Soviet. What are some of the interesting takeaways and lessons you had looking into how America tried to grok the Soviet Union?

Hal Brands: In some ways, I think we’re a little bit better off today than we were at the beginning of the Cold War.

I think it was Richard Helms who later wrote, “in the beginning, we knew nothing.”

We had a few dozen Soviet analysts in the United States. George Kennan was a brilliant guy, but one reason why he seemed so brilliant was that nobody else knew anything about the Soviet Union.

You couldn’t travel there. It was difficult to get basic information about the government and the economy. So he stood out because he was a big fish in a very small pond. I think we’re in better shape today: we have a lot more China expertise in the United States now than we had Soviet expertise in 1947.

Do we have more China expertise in the United States than we had Soviet expertise in 1971 or 1983? Probably not, because we haven’t made the same generational investments in that expertise that we did during the Cold War. I also worry that some of the expertise we have either isn’t in the areas where we would want it to be, because the Chinese have created really good disincentives to aspiring academics studying particular aspects of Chinese politics and society, or maybe some of it is a waste in assets because it’s getting harder and harder for people to go to China to do fieldwork.

But I think what the Cold War does teach us is that you can overcome this: it just takes a lot of time, a lot of money, and a lot of energy.

And that’s what we did during the Cold War: we basically created an entirely new academic field of Sovietologists. You had academic institutions, philanthropic foundations, and government all come together to create the money and the brainpower you needed to really study a very hard target from an intelligence perspective.

This is really when it becomes common for academics to go between academia and government, or for people to spend time at Rand or Brookings, and then serve as consultants for the executive branch. Over time, I think the strength of that arrangement helped us create a very deep pool of Soviet expertise. We didn’t always have all the expertise we needed and I’m not claiming that the record was perfect in any way, but we also created a nice ecosystem where real debate could occur.

This was one of the great differences between the US and Soviet approaches to intelligence. The Soviet Union was clearly better than us at human intelligence, for instance, but they were terrible at analysis because there was no incentive to engage in honest debate or criticism within the Soviet government.

It was different in the United States. We had a de-centralized approach to intelligence in a way that would pit different intelligence institutions against each other. You had outside experts who could argue with the government when they thought the government was getting things wrong. Overall, if not in every circumstance, I think that improved our hit rate over the course of the Cold War.

Jordan Schneider: There hasn’t been much room in academia for folks doing Pekingnology and writing about the party qua the party, which is a real misstep. That’s something that, hopefully, both the US government and philanthropic money start to address them.

Hal Brands: One of the things we eventually figured out during the Cold War was that it costs more not to have this expertise than to have it. By the time you get to the later parts of the Cold War, in administration after administration, you’re seeing specific cases of this payoff. You look at Zbigniew Brzezinski, the National Security Advisor under Carter and a product of American Sovietology; Richard Pipes, a product of American Sovietology; Jack Matlock, same deal. They were running incredibly important parts of US policy while drawing on this intellectual capital that the country had invested into.

Emily Jin: One of my hypotheses of why there might be a lack of super concentrated expertise or analytical energy going into this, besides everything that you mentioned (which I agree with), is this idea that maybe the United States has forgotten how to deal with tragedy.

I’m, specifically thinking about your 2019 book with Charles et al., where you talk about the Athenians looking at tragedy as a vehicle for collective action. How receptive is the American public and the American government to prolonged competition today? How does that influence the investment that goes into this expertise?

Hal Brands: I think our problem is we’re pursuing Cold War objectives with post-Cold War levels of urgency and investment.

We have convinced ourselves that we face a problem in China and Russia, but I don’t know that we have been honest with ourselves about what level of investment, energy, and sacrifice it’s going to be.

It’s going to be necessary to deal with those problems effectively, because as you say, we’ve forgotten how bad the penalty is for getting these things wrong in a way that the WWII generation would have found much more difficult to forget. Now, maybe the Ukraine crisis is helping to remind us of this a little bit, and the Chinese seem determined to remind us of it with some of the more outrageous things that they do.

But I do think this is a real problem. It’s one thing to say that you’re doing great-power competition. It’s another thing to do it effectively. I think we’re between those two things at the moment.

Economic Determinism: How Much Does Wealth Matter?

Jordan Schneider: At the end of the day, the balance of the offering America had to the rest of the world and to the Soviet people, just by having a GDP per capita multiples ahead of what the Soviet system could offer, seemed to be the trump card that a lot of these debates came down to. How much does the marginal stuff matter, relative to just making sure that you’re the richer country than your adversary?

Hal Brands: Being rich, powerful, and attractive is rarely a disadvantage, in geopolitics as in life. In 1945, the United States had half of global production because the rest of the world had been destroyed after WWII. So the story of the first 25 years of the Cold War was everybody else catching up with the United States. For the most part, that’s a good thing because a lot of the countries catching up with us were Japan, West Germany, and other allies. So that actually strengthens us in the Cold War.

World powers’ respective shares of global GDP, from 1AD to the present. Notice the US’ peak near 1950. (Source: World Economic Forum)

I think you can make the argument that so long as the Western world held together, it was going to win in the end because the power imbalance was so severe, but it wasn’t a given that the Western world would hold together. The Western world could have fallen apart in the late 1940s, if you had economic collapse in Western Europe and a bunch of communist parties had come to power; in the early 1950s, had you not strengthened NATO and fortified the hard power backbone of the free world. There are a variety of times in the 1970s, for instance, when it looked like the Soviet Union was getting the advantage.

No matter how rich and powerful and attractive you are, there still come these critical junctures where it takes good, bold, or prudent decision-making to get what you need.

Kill Adversaries With Kindness

Jordan Schneider: One of the chapters that I really liked was the one on the conclusion of the Cold War, and how Reagan and George H.W. Bush in the closing years of the conflict killed with kindness. What went on in 1984-92?

Hal Brands: Because Soviet power was collapsing in the 80s and early 90s, Americans were playing pretty ruthlessly, but they were also going out of their way to make sure that they did not humiliate a weakened superpower and to give Gorbachev the sense that he could strengthen his own prestige and position through a partnership with the West.

Reagan uses a lot of pageantry at summits and things like that, to send Gorbachev the message that if you change Soviet foreign policy in ways that we deem constructive, you will be welcomed back into the world as a legitimate member of the international community. Bush goes out of his way to portray Gorbachev as a partner in the diplomacy surrounding German unification in 1990 for exactly the same reason.

Over time, Gorbachev comes to see that his best alternative lies in giving the West a lot of what it wants.

Because it’s giving him some of what he needs as well: prestige, economic resources, and other things. It’s ultimately a pretty ruthless policy, where we get everything we can out of Gorbachev while he is still in power. But one of the reasons that it’s acceptable to Gorbachev is that we treated him with a lot of kindness.

Photo of Reagan and Vice President Bush meeting Gorbachev at the Governors Island Summit on December 7, 1988. (Source: National Archives)

Jordan Schneider: Thinking about that and the lessons with regards to the war in Ukraine, as hard as it: unless Putin gets toppled (which, maybe there’s a 10% chance), he’s going to be the one that’s going to end this war. The lessons from that moment of figuring out how to give folks off-ramps is a tricky thing to think about, especially when you see the images you see on TV, but that’s important when understanding how conflicts end.

Hal Brands: It’s particularly difficult because you’ve got to create enough pain that Putin wants the off-ramp first, then offer the off-ramp once he believes that it’s desirable to take it. That balancing act is particularly tough.

Book Recommendations

Hal Brands: One book I’m reading right now is called Autumn in the Heavenly Kingdom by Steven Platt. It’s a masterful account of the Taiping Rebellion in China in the 1850s and 1860s, which was a much bigger global deal than anybody remembers. The reason it’s relevant today is it actually has some long-lasting implications for what you might think of as the Chinese worldview. It’s useful in understanding the historical background to Chinese decision-making.

Another book that I was just leafing through this morning is an oldie, but a goodie: it’s John Gaddis’ Strategies of Containment, which was first written in the early 1980s. It was the first book to systematically study American strategy during the Cold War. I’m biased — he was my dissertation advisor — but every time I read it, I’m still impressed by the number and the quality of the insights in there.

Tyler Durden

Mon, 08/01/2022 – 23:40

Recent Comments