“Superheroes” Reflect Our Powerlessness

Authored by Charles Hugh Smith via OfTwoMinds blog,

And so we end up back in MovieLand, where we vicariously experience having powers we do not possess in real life.

Films reflect the collective unconscious in ironic ways. During the Great Depression, films didn’t dwell on the miseries of real life; they were carefree concoctions making light of the idle rich (The Thin Man, 1934, My Man Godfrey, 1936), with the realistic (but still ending on a positive note) The Grapes of Wrath arriving a decade into the Depression in 1940.

In contrast, the boom years of the 1950s were the heyday of dark-themed Noir films that explored (and exploited) the underbelly of human nature and American life.

Cast in this light, what do we make of our multi-decade cultural embrace of Superhero films? We can try to write it all off as Hollywood’s happy discovery of an entire realm of “tentpole” franchises that can be milked for billions of dollars in reliable revenues, but this misses the undertow of cultural significances.

Is it coincidence that the decades of Superhero worship track the rise of our collective powerlessness over the shape of our future? I sense the outrage and indignation this ignites–how dare you say we’re powerless, we have more power over our lives than ever before.

For a contrarian view, let’s tap the 1964 classic by Jacques Ellul, The Technological Society (this link is to a free PDF of the book, with gratitude to correspondent Bruce M. for bringing this book to my attention). It is impossible to summarize a 500-page book dense with important ideas, but let’s start with Ellul’s insight into our collective powerlessness over the future course of the economy and our own daily lives.

In essence, Ellul explains how technology and the ever-expanding need for profitable investments control our collective future. Once the basic human needs have been met–shelter, food, water, education, medical care, etc.–then investment opportunities aren’t driven by human need, but by technology’s continuous advance.

Did humanity really “need” every appliance to have WiFi? No. Technology generated WiFi and the need for investment opportunities then generated The Internet of Things (IOT) which spawned vast new product lines–appliances with WiFi. Coupled with the the collapse of quality and durability, this technology led to water heaters having WiFi, just in case your phone doesn’t have enough apps, alarms, chirps and notifications.

That water heaters once cost $160 and now cost $500 is the financial payoff of advancing technology creating new opportunities to invest capital. For if capital can’t find new opportunities to invest and grow profits, the economy slides into Depression, and that ghastly prospect looms in the collective unconscious as the nightmare to be avoided at all costs.

And so microwave ovens now have a second “child safety button” that must be pushed first to open the door. Safety is a ready-made excuse for adding whatever technology has come up with, and as we scan the horizon, it’s already abundantly clear that the tens of billions of dollars gushing into AI will be followed by trillions of dollars seeking higher profits from putting some simulacrum of AI into every device, every appliance, every app and indeed every technology, not because it improves our well-being but because it’s the investment opportunity that we desperately need to avoid the cataclysm of Depression.

We are powerless to question this process, much less resist it, and so we revel in fantasies of super-powers that enable the defeat of powerful forces that threaten us. That AI will automate away entire sectors of human livelihoods–we’re powerless to resist that, just as we’re powerless to stop the collapse of durability and the Anti-Progress of useless complexity and the ever-greater demands on us to perform unpaid shadow work to keep all the complexity duct-taped together so we can maintain all the technologies that we are now dependent on, not by choice but because there is no choice.

The cavalcade of superheroes reflect our powerlessness and our yearning for actual control of our lives rather then the simulacrum of consumer choice of products and services that don’t serve our well-being, they serve the one true need, to expand opportunities to invest.

Ellul’s insights from 60 years ago also illuminate our desire for real-world political-financial Superheroes who will set the world right again. But political solutions are another form of fantasy, as I explained in Why Political “Solutions” Don’t Fix Crises, They Make Them Worse (10/2/24). Hoping that giving other mortals power will restore our own power over our own lives is akin to hoping that technology will magically transform itself from humanity’s Monster Id into a machine that oversees us with loving kindness, or as poet Richard Brautigan put it, All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace.

Sci-Fi movie fans know that the Monster Id is from the classic film Forbidden Planet: the limitless power of the planet’s immense technological machinery is guided by thoughts, and since there are no filters on what thoughts guide the technology, all the dark drives of the Id are amplified by technological powers, such that the Monster Id melts solid steel doors like butter in its quest to destroy the mind that created it.

And so we end up back in MovieLand, where we vicariously experience having powers we do not possess in real life. The power we still have is not a superpower; it is a merely human power to opt out, to choose not to participate, to limit our exposure to a world guided by investment opportunities and the moral vacuum of technology that is blind to all but its own advancement.

That all technological advancement is good is, well, a lie. Much of what’s presented as Progress is actually Anti-Progress, a theme of my new book The Mythology of Progress, Anti-Progress and a Mythology for the 21st Century.

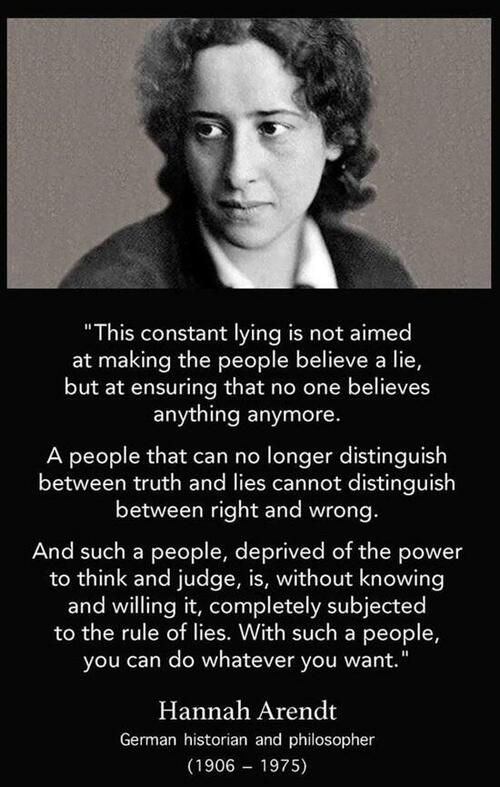

If all we believe boils down to “technology good, investment opportunities good,” then we’ve relinquished the ability to distinguish between truth and lies, and as Hannah Arendt observed, the difference between right and wrong.

This too is powerlessness, a black hole from which there is no technological escape.

* * *

Tyler Durden

Tue, 11/26/2024 – 20:05