Machiavelli’s Sage Advice To Transformational Leaders

Authored by Charles Hugh Smith via OfTwoMinds blog,

Machiavellian has negative connotations–cynically unscrupulous scheming to gain or maintain power–but this misses the mark of Machiavelli the man who sought a livelihood in the cutthroat political street fighting of Italy’s city-states circa the late 1400s and early 1500s.

As he made clear in other writings, Machiavelli favored democracy over competing political arrangements, and he wrote The Prince (the entire book in PDF format) as a sort of extended resume seeking to bolster his chances for employment.

First and foremost, Machiavelli explores the psychology of power and leadership. For leaders who seek to change the polity rather than merely maintain the status quo, Mr. M. lays out the challenge facing transformational leaders in Chapter Six of The Prince:

Here we have to bear in mind that nothing is harder to organize, more likely to fail, or more dangerous to see through, than the introduction of a new system of government.

The person bringing in the changes will make enemies of everyone who was doing well under the old system, while the people who stand to gain from the new arrangements will not offer wholehearted support, partly because they are afraid of their opponents, who still have the laws on their side, and partly because people are naturally skeptical: no one really believes in change until they’ve had solid experience of it.

So as soon as the opponents of the new system see a chance, they’ll go on the offensive with the determination of an embattled faction, while its supporters will offer only half-hearted resistance, something that will put the new ruler’s position at risk too.

In other words, those who are diminished by the proposed reforms will resist with all their might, while those who might benefit are lukewarm in their support because the benefits of the reform are not yet in hand. Put another way, one person’s efficiency reform is the loss of a livelihood / gravy train to another, and the gains of the proposed efficiency are 1) in the future, while the livelihood is threatened in the present, and 2) the gains of the efficiency are disbursed over the entire populace, so that the recipients of the reform have little incentive to fight tooth and nail like those defending their slice of the status quo pie.

This presents the transformational leader with a difficult choice of strategy: the first option–to attempt a wholesale transformation of the status quo in a Big Bang reformation of every agency and institution’s budget, leadership and culture–is tempting, as the political capital of the new leadership is strongest at the start, before its opponents have had time to chip away at the new administration’s support.

The second option is to choose one or two critical reforms and devote every ounce of political capital to pushing these through. This option is less grandiose, more cautious, but it’s also the one most likely to succeed, as the risk in Option 1 (The Big Bang blitzkrieg) is that the political capital of the reformers will be diluted by engaging the armies of opposition that will arise in every threatened agency and institution.

The benefit to this strategy is one or two big wins at the start solidifies the political support of the reformers. Supporters will see significant victories as proof the reformers are sincere and their power is sufficient to push through reforms despite the resistance of incumbents / special interests.

On the other hand, the incremental approach of winning a few key battles at the start might miss the opportunity to bulldoze all opposition before they can organize resistance. Much depends on the general zeitgeist of the time. If those benefiting from the status quo believe the system is sustainable as is, they will fight tooth and nail to water down reforms to protect their gravy train.

If the status quo is crumbling, then insiders are incentivized to make a deal with the reformers as a better option than losing everything as the system unravels beneath their feet. It also matters if the general public and movers and shakers are solidly behind the reformers, or if their popular support is an inch deep and a mile wide.

Machiavelli’s advice to transformational leaders is: don’t underestimate the fierce resistance of those losing their grip on power and all the financial rewards of that power. Be prepared to use every trick in the book to dilute and fragment opposition: buy off those who can be bought off, offer face-saving deals to key players, compromise to get key changes, set opposing factions against each other, and be generous and humble in victory rather than triumphant.

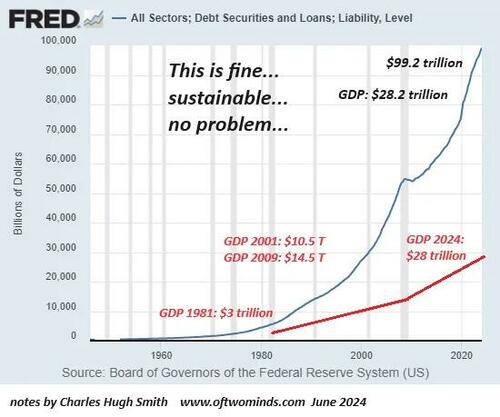

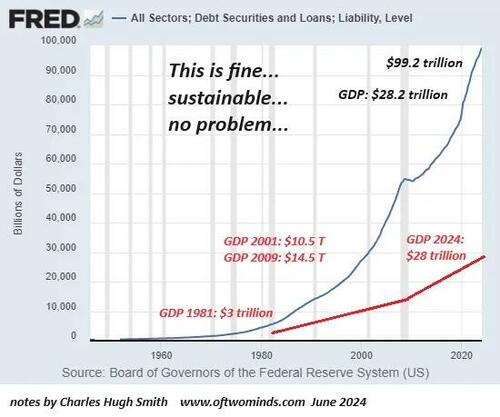

Looming over the entire reformist enterprise are the costs and risks posed by debt. Living on borrowed money is splendid in the beginning, when the cost of servicing the debt is low. But as the debt mountain grows, the cost of servicing the debt incentivizes borrowing more to pay the interest, accelerating the expansion of debt in a self-reinforcing feedback.

The cost of servicing the debt soon squeezes out other expenditures, and the borrowers’ incomes no longer support investing and spending on the scale to which they’re accustomed. The solution is of course to borrow more, and pass through the portal to the Magical Kingdom of Magical Thinking where we believe that we can “borrow our way out of debt” because borrowing more will enable us to “grow our way out of debt.”

Once the mountain of debt is towering, this notion is fantasy. The only sustainable options are painful: 1) devalue the currency, wiping out both the debt and the currency’s value, 2) tighten our belts and pay down the debt by reducing consumption, or 3) default on the debt and absorb the enormous losses, as every debt is somebody else’s asset.

That choice already looms large, and reformers must reckon with that as well as their reformist agenda. Here is total debt:

Here is federal debt:

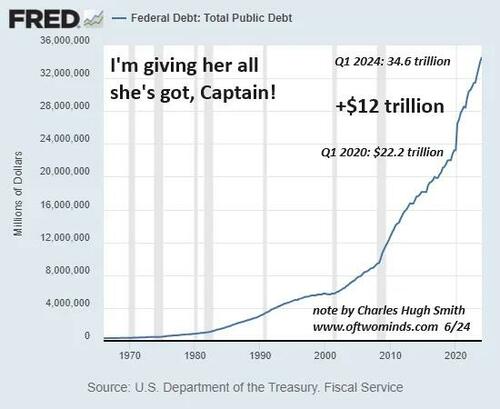

And no, we’re not going to be “saved” by interest rates going back to zero: higher for longer is the future, as bond yield / interest rates cycles are multi-decade affairs.

Zero interest rate policy (ZIRP) was delightful in the moment but the full consequences of that stupendous error have yet to play out.

Tyler Durden

Thu, 11/14/2024 – 05:00