Central Planning: China’s Miracle… And Malaise

Authored by Charles Hugh Smith via OfTwoMinds blog,

The illusion created by the initial success of central planning is that it can continue indefinitely, when the reality is it’s unavoidably self-liquidating as the distortions unravel the entire economy.

China offers a real-time case study of the upsides and downsides of central planning, broadly defined as the central state establishing the goals, financing, incentives and regulatory structure for various sectors of the nation’s economy.

In the U.S., examples include the transformation of the American economy to wartime production in World War II, and the razing of inner city neighborhoods to build freeways in the 1960s. A swath wasn’t just bulldozed in one or two cities; it happened everywhere because the federal government established the funding and incentives.

Turning to China: those of us who were fortunate enough to visit China just before the “China miracle” took off recall the decrepit state of China’s housing stock, much of which was unchanged from the 19th century except for electrical wires strung haphazardly through dimly lit common areas.

Starting in the 1990s, China’s central government began selling land leases to households, retaining ownership but granting lessor ownership rights to those living in the homes, in effect transferring ownership from the state to households. The idea wasn’t to create an asset that households could sell, and so after-market sales were non-existent. The idea was to shift the cost of housing from the state to the private sector, freeing up state funding for industrialization and infrastructure.

As China’s economy shifted from rural agriculture to urban industrialization, the need for urban housing became a priority. As tens of millions of people left rural villages for factory jobs in cities, a new centrally planned model emerged that from the perspective of the central government was a win-win-win:

1. Local governments were given the right to sell land to housing developers, and the revenue from these sales eventually made up between a third and half of local governments’ budgets. In effect, a third or more of the costs of local government were shifted from Beijing to the private sector.

2. Construction of housing–much of it in high-rises–created millions of jobs, so roughly 10% of the workforce was employed in construction. This employment boosted the nation’s economy, a key goal of central planners in Beijing.

3. As China’s economy boomed, central planners prioritized bank lending for housing, enabling households to deploy their accumulated savings to buy a home (or later, an investment flat), a culturally favored “safe” asset to invest in.

Note that housing was funded by private capital in this model: developers pre-sold homes to households, who used their savings as the down payment and borrowed the rest from banks (often closely tied to the government). The buyers paid for the home in full, so developers had all the money upfront, and the temptation to use these funds to buy more land leases for future development and pre-sell more to-be-built-later homes was Irresistible.

Since the sale of existing units would compete with new construction, there was no resale housing market as in the West. The value of existing units was set by new housing being sold/built in the area. So if a household bought a unit for $100,000, and the new development next door was selling for $150,000, then the existing homeowners reckoned their home was now worth $150,000 as well.

This artificial valuation generated a wealth effect–our homes are rising in value–that was entirely illusory, an illusion that has burst as the actual resale value of homes was never tested in an open, transparent marketplace.

As a result, this artificial wealth effect has flipped into a reverse wealth effect: households are awakening to the grim reality that their real estate-based wealth has evaporated, and given the extreme oversupply of housing and the declining population, it’s never coming back.

With few other investment opportunities available, households poured their savings into investment homes, usually leaving them empty, as homes that had been rented to tenants were considered of lower value.

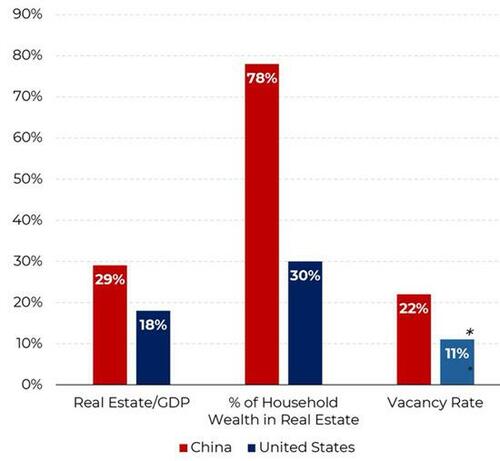

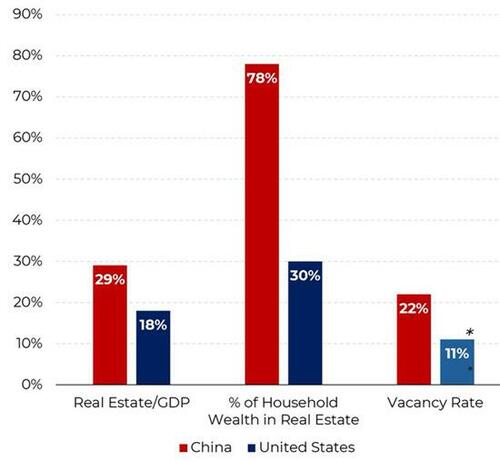

As a result of this model, housing now comprises 70%+ of all household wealth, a percentage more than double that in the U.S. (30%):

But central planning’s initial successes generate a blindness to its fatal flaws, a reality now playing out in China’s housing sector. The model described above created “winners”–banks, developers and local governments–who have every incentive to continue building more developments, whether they fill a real need or not, and no incentives to recognize the diminishing returns and soaring risks generated by the model.

Without an unfettered, open resale market for homes, the actual value of existing housing is unknown. Since the model only wants buyers of new (and as yet unbuilt) homes, the resale of older homes is suppressed. As a result, there is no feedback as to whether more developments actually fill a need for housing, or if they are nothing more than stupendous mal-investments, black holes sucking in capital, resources and labor that could have been productively deployed elsewhere in the economy.

Two recent reports outline the malaise once the central planning “miracle” becomes a blind machine enriching entrenched interests, grinding on even as the vast asset bubble the “miracle” created is popping:

China’s Paradox Under Xi – Episode 2

Since there were no feedback mechanisms allowed in the model, it continued expanding regardless of actual conditions. The net result is a massive debt bubble and an equally massive oversupply of housing: thought official statistics are not published (for the obvious reason that they reflect poorly on central planning), it’s estimated that there are 94 million empty homes in China and an astounding 120 million paid-in-full homes that are unfinished or not yet started. That’s an oversupply / overproduction of 214 million homes.

Whether the actual number is 160 million, 180 million or 220 million doesn’t really matter at this point: the oversupply, losses and distortions are so vast that there are no pain-free policy tweaks that will fix what’s broken or reverse the catastrophic losses.

Since the developers used the buyers’ funds to buy more land leases, they no longer have the means to complete the 100+ million units promised / under construction. The central government is now on the hook to fund the completion of these millions of homes–many of which were investments, not intended for sheltering a family–and to clear up the enormous debts left by insolvent developers.

Who suffers the most is obvious: the hapless home buyers who are paying mortgages for half-finished homes that may never be completed. The net result is some of the homeowners are living in their half-completed high-rise homes, as shown in the video from BBC News, in which the filming was cut off by local police, as this tragic reality doesn’t reflect well on central planners:

China’s homeowners living in unfinished apartments BBC News (3:21 min)

Given the enormous over-supply and collapsing demand, what’s known as a bidless market, the actual market value of older homes may well be near-zero in Tier 2 and 3 cities, as the costs of ownership exceed the return on the investment. Without paying renters or appreciation generated by scarcity, the value of an existing home is a negative number.

What lessons can we extract from the success and failure of this model?

1. When an economy has untapped productive capacity and is starved for credit, central planning can open the floodgates of credit and direct the productive capacity into specific sectors, creating rapid growth and “winners”: in China’s real estate boom, the “winners” were banks, developers and local governments, as well as the central government freed of the immense burdens of funding the construction of hundreds of millions of new homes.

2. The “winners” quickly become entrenched in the system, rewarding each other with kickbacks, insider trading, etc., and as their wealth grew, so did their political muscle, which they used to protect their sector from oversight or feedback from the real world.

3. China’s central planners reckoned they’d discovered the financial equivalent of the perpetual motion machine, that housing would continue to provide 10% of the nation’s jobs, fill the coffers of local government and enrich insiders indefinitely, all paid for with private capital saved up by households.

4. There were no effective safeguards in the system to protect homeowners from paying in full for a never-built or half-finished home. Central planning incentivizes insiders and entrenched interests to play fast and loose to maximize their private gains, without regard for the distortions and systemic risks their wheeling and dealing generates.

5. Since market mechanisms were eliminated or restricted, there are no structural mechanisms in either the private sector or the central government to fix the machine once it implodes. The immense losses piling up under the surface eventually must be paid by someone, and so central planners, faced with insiders’ outsized influence, end up distributing the losses to the powerless, i.e. households, workers, children, retirees, etc.

This eventually generates social malaise, and the decay of the consent of the governed (a.k.a. Mandate of Heaven).

The inherent weaknesses of central planning are on display in every economy. It’s tempting to use central planning to kickstart a sector or industrialize / re-industrialize, but there are no mechanisms in central planning to recognize or respond to the fact that you can only funnel private capital into a blind machine of entrenched interests for so long before the machine consumes not only all the gains of central planning but the entire economy, as the distortions become so profound that there are no fixes other than the extreme pain of absorbing catastrophic losses.

The illusion created by the initial success of central planning is that it can continue indefinitely, when the reality is it’s unavoidably self-liquidating as the distortions unravel the entire economy. As I explained in my weekend post for subscribers, TINS and the Global Economy’s Cliff Dive: There Is No Substitute, once the central planning model reaches its inevitable point of failure, there is no substitute available, as the economy has been optimized to reward the “winners”, effectively hollowing out other sectors of the economy.

I was invited to discuss the upsides and downsides of central planning on two recent podcasts: there is quite a lot of ground covered in each discussion, please give them a listen:

* * *

Tyler Durden

Wed, 11/06/2024 – 12:05