UK Gilt Yields Soar After Reeves Reveals Budget: Market Braces For Inflationary Debt Surge

Ahead of today’s UK budget announcement, much of its content had already been leaked including the biggest novelty item: redefining the concept of debt, to allow the UK – which already exceeds the 90% debt-to-GDP threshold that Reinhart and Rogoff estimated to be the point at which the Keynesian multiplier falls below one and which means that for every extra dollar that the government spends GDP increases by less than one dollar – to borrow an additional $90 billion in debt, a gimmick which only a politician could possibly have though was a good idea (and the US of course, but at least the US still has the reserve currency, something which the UK enjoyed a century ago until it lost it).

And while there were indeed no major surprises, the market clearly was not impressed with what it saw and has sent gilt yields soaring, sparking some concerns that another Sept 2022 “minibudget” crisis may be on the horizon.

But first, here is a snapshot of what we learned:

As Bloomberg reports, UK Chancellor Rachel Reeves unveiled £40 billion ($51.8 billion) of tax hikes, the most in decades, and massively ramped up borrowing (largely thanks to the new debt definition), both seismic moves designed to meet Labour’s pledge to “rebuild” the UK that still yielded only modest projected boosts to growth and public spending.

The budget was a make-or-break moment for both Reeves and Prime Minister Keir Starmer that will define their government. The scale was eye-watering, from the extra £142 billion of borrowing over the Parliament to tax rises that were the most in at least 30 years, when former Tory Chancellor Norman Lamont was also trying to restore economic stability. Labour’s inheritance from the Conservatives dominated Reeves’ narrative that offered a glimpse of the likely battle lines ahead of the next election still five years away.

Reeves put the tax burden on course for a postwar high with hikes impacting businesses and the wealthy in particular, insisting she had no choice but to fill a fiscal hole left by her Conservative predecessors if Labour was to deliver on its election pledge to begin a decade of national renewal. To bolster the impression that mostly wealthy people would bear the brunt, Reeves also decided to freeze fuel duty, increased the minimum wage and unexpectedly ended a freeze on income tax thresholds introduced by the Conservatives.

Despite the staggering tax hikes targeting the rich, which will inevitably lead to a scramble of rich expats fleeing the UK for low or no tax regimes such as the UAE, Reeves’ intervention still risked leaving voters unsatisfied. Estimates by the Office for Budget Responsibility appeared to fall short of Labour’s manifesto pledge to have the highest growth in the Group of Seven, and day-to-day public spending will rise just 1.5% per year, with several government departments facing real terms cuts. The question of whether the numbers justify a backlash especially from businesses will dominate the coming weeks.

In her statement, Reeves took aim at the Conservatives and especially former Chancellor of the Exchequer Jeremy Hunt sitting across from her: “The scale and seriousness of the situation that we have inherited cannot be underestimated,” said Reeves, the first female chancellor to deliver a budget in the 800-year history of the role. “Any chancellor standing here today would face this reality, and any responsible chancellor would take action.”

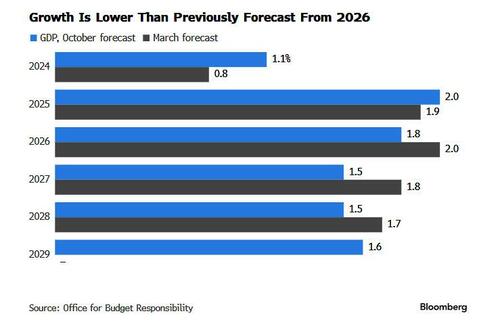

This was duly followed by a slashing of GDP growth estimates, which were cut for the nearby years, offset by the now traditionally increase in outer years, which of course will never happen.

More worrisome is the inflation forecastL while the BoE’s mandate is reconfirmed as 2.0%, the OBR doesn’t see that occurring until well beyond the end of the BoE’s forecast horizon; in fact, the OBR has CPI at 2.0% in 2029.

- 2024: CPI 2.5%

- 2025: CPI 2.6%

- 2026: CPI 2.3%

- 2027: CPI 2.1%

- 2028: CPI 2.1%

- 2029: CPI 2.0%

Of course, the risk is that this is very much incorrect and that UK inflation will not only not drop after 2025 but continue rising, crushing the budgeted model, and forcing the BOE to hike far sooner than expected.

And yes, as we previewed, Reeves also changed the debt measure targeted by the government for its other fiscal rule – which requires debt to be falling as a share of the economy – to give herself space to borrow for investment. The government will now target public sector net financial liabilities instead of public sector net debt excluding the Bank of England, she announced. Here is how UBS described the debt switcheroo:

[Reeves] confirmed the measure of debt will switch to net financial liability. In doing so she is able to pull in a number of assets to the calculation. She said the net financial debt rule will require the measure to be lower in the final year of the horizon relative to the year before. She will reduce the time horizon to three years from five years in 2026/27, and then roll onwards such that debt must be lower in each consecutive year from 28/29 onwards.

But while the public takes its time to assess the social impact of the Labour budget, the market’s reaction was swift and brutal as UK gilt yields soared as traders digested the long-term ramifications of taking on so much debt with a smaller than expected fiscal cushion. After earlier dropping as low as 4.20%, the 10Y Gilt surged over 20bps higher, and briefly touching 4.411%, the highest level since last November.

Curiously, markets were relatively muted while Reeves was speaking, and in fact there was an oddity in the market reaction: the yield low point during the budget speech was achieved at the moment Reeves reported tax hikes would total £40 bn. The market narrative at that moment was on the downside growth consequences. But right after that, bond yields soared as investors balked at the prospect of historically high debt issuance and fiscal stimulus that could mean interest rates stay higher for longer. The Debt Management Office said it will issue £297 billion of government bonds in the fiscal year 2024 to 2025, broadly matching the £293 billion estimated by 16 bond dealers in a Bloomberg survey. Of note, the DMO added £22.2 bn to its funding requirement for the current fiscal year, with the increase funded by additional Gilt sales of £19.2 bn, taking planned total Gilt sales in 2024-25 to £297 bn; and an increase in net (cash) sales of Treasury bills for debt management purposes of £3.0 bn, taking the planned net contribution to financing from such bills in 2024-2025 from zero to £3.0 bn.

The upward move in gilt yields, with shorter-end yields leading, led to a bull flattening indicative of a market reassessing the BOE’s reaction function in the face of greater inflation risks, i.e., not only are the days of rate cuts numbered, but inflation may return much sooner than expected, prompting the next hiking cycle by the BOE.

After the announcement, the UK’s OBR emphasized the fiscal loosening inherent in the budget, continuing the pattern of expansionary government policy in recent years, but the bond market may have had its “lettuce” moment and any incremental debt increases from here on out will only lead to a faster blow out in yields and lead to another debt crisis.

Commenting on the blowout in yields, UBS said that “UK markets opted to focus on the inflationary consequences of tax hikes. The thinking goes that since businesses are doing all the heavy lifting on taxes, that they’ll just pass that on to final selling prices. In that respect, the budget becomes inflationary. The market then talks itself into the idea that the BoE won’t be able to cut rates – they wouldn’t dare say “transitory”, which is what tax effects are on inflation.”

To this UBS counters that the alternative version is one taken from a traditional economic textbook, namely that higher end-prices represent a supply shock that causes spending to slow down; the Swiss bank suggests that the budget should be considered a Gilt twist steepener: “The upfront tax rises causing consumption to slow; the longer-term issuance driving term premium higher. If one wanted to make the link to the BoE, then it would be to buy into the improved long-term growth potential from higher investment in the future.”

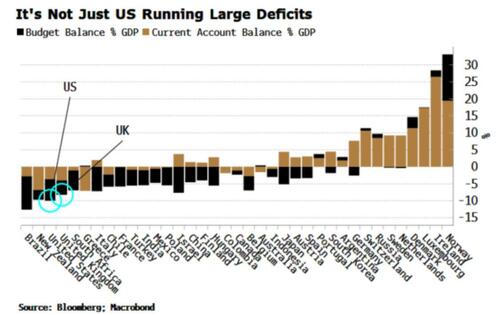

Others were less sanguine than UBS, with Bloomberg’s Simon White focusing instead on the overall (catastrophic) fiscal picture that the massive new debt layring will result in; he said that while much focus is on the US’s soaring budget deficit, the UK’s is also egregious. When the current account deficit is added, the US and UK run almost the largest twin deficits in the world.

Indeed, debt has always been the UK’s Achilles’ heel. That’s because while the US has the world’s reserve currency, the UK doesn’t have that privilege, only an ability to print as much of a currency that fewer and fewer people want. That’s potentially very inflationary in the longer term, and that’s precisely why the market is reacting the way it is.

Bottom line, as White puts it, markets are once again waking up to the likelihood that rates in the UK aren’t likely to fall as much previously expected, or the BOE would want, and should the blow out in yields continue, we may be just days away from another emergency QE action by the BOE in the past two years as the world is reminded that the only reason why the US can and continues to borrow like a drunken sailor, is because it still has the world’s reserve currency, although judging by the explosion in gold and bitcoin in recent days, that won’t last long.

Tyler Durden

Wed, 10/30/2024 – 13:05