Income Inequality And Social Security

Authored by Brenton Smith,

Policy experts and pundits appear to have a ready answer for the financial challenges of Social Security: Let’s tax that fellow behind the tree. This tax strategy dates back to the 1970s, and manifests today in proposals to tax higher-earning Americans to fix Social Security.

Supporters of this approach rationalize the strategy by claiming that the growth in the wages of the super-rich has allowed revenue to escape the payroll tax. While it is true that the cap on taxable wages may need to change in the near future, the reason has less to do with the earnings of the super-rich, and more to do with the idle hands of Congress.

Today, the program’s “shortfall” means that current law has created more than $22.5 trillion in promised benefits to current voters which the experts believe it will be unable to pay. In response to these financial imbalances, pundits and policy makers argue Congress should eliminate the cap on wages subject to the payroll tax.

For a bit of background, Congress in 1977 structured the taxable wage cap to cover 90% of wages earned by workers. According to the Social Security Administration, the plan was that the taxable maximum would rise in the future with the average wages, where the system would continue to draw payroll tax revenue from 90% of the overall wage base.

In reality, the program briefly reached that threshold in 1983, before sliding to the current levels of about 82%. About half of the decline occurred between 1983 and 1988. The balance of the fall occurred prior to 2000. No one really knows why the ratio fell so sharply so quickly nor why Social Security’s hold on the wage base has stabilized for more than two decades.

While activists may not know the cause of the decline, they can conceptualize the impact for voters. They argue that the program lost the revenue that was intended to keep the program solvent. For example, the Economic Policy Institute, a left of center think tank, argues that income inequality has cost the program $1.4 trillion (including interest).

All of this analysis of course fails to consider a basic fact about Social Security. Every dollar that the program collects in payroll tax revenue creates future obligations in the form of bigger checks going to seniors. Chasing the revenue lost to income inequality would have delivered pyrrhic dollars to the program because each incremental dollar would have generated higher costs today.

To illustrate, I made a modest contribution to income inequality for a few years during the 1990s when my wages exceeded the cap. Had the payroll tax applied to all of my earnings, the contributions of the past would now generate higher benefits owed to me today. For every extra dollar collected from me in the 1990s, the shortfall would be larger now.

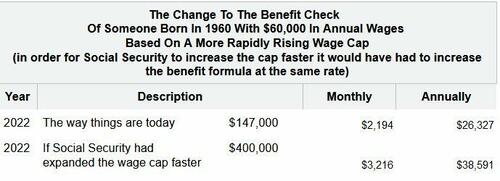

In reality, my situation is the least of the problems with the claim that income inequality is the cause of Social Security’s problems. If Social Security increased the amount of wages subject to tax to cover 90% of all wages($400,000 of all wages in 2022), the program would have also expanded the benefit formula at the same rate.

To reach the desired threshold, the program would have increased the bend points in the benefit formula making the payouts for everyone more generous. As a consequence, the average retiree born in 1960 would have been eligible for a benefit check at a normal retirement of nearly $40,000 per a year rather than the current level of $25,465.

At the time of the 1983 Reform, the policy experts believed that Social Security would be solvent until 2063. Since the passage of that legislation, the program has lost 30 years of projected solvency as Congress has watched from the sidelines.

Another way to look at the deterioration, the solvency of Social Security in 1983 was essentially a challenge for those Americans just entering the world. Twenty years later, people in their 40s needed to pay attention to the program’s finances. Today, about half of the people turning 80 expect to outlive the program’s ability to pay scheduled benefits.

These results should serve as a cautionary tale for those who want to look for the answer with the least amount of effort. These projections are not a guarantee. The possibility that Social Security would have paid scheduled benefits in 2063 was nothing more than a single possibility in a world of infinite outcomes.

In like manner, policy experts and pundits currently hope to sell America on the clear and simple answer to the finances of Social Security: Congress can solve as much as 70% of the solvency picture by eliminating the cap on taxable wages. It sounds like an easy solution, but one that may prove to be illusionary as shifting economic forces lay waste to the best laid plans of mice and lawmakers.

Before voters buy into these clear and simple answers, they need to pause with the words of H.L. Mencken. To every complex problem there is an answer that is clear, simple, and wrong.

—–

End Notes

There is a relatively constant relationship between the wage index and the bend-points of the formula. The first bend point is 1/143.xth of the wage cap, and bend-2 is roughly 1/23.8th. The ratios have been roughly the same since 1983. Happy to send that chart again.

I used 2022 because it is the latest hard wage data. 2023 isn’t available until October. I used the $25,465 figure because it comes from the SSA.

In the report, the normal retirement age in 2022 was 66 ½. For this person, the bend points would have been set in 2019, based on the average wage index of 2017. That is difficult to replicate. That mix is complex so I used roughly $40,000, rather than exact figures.

My chart shows someone who was born in 1960, turning 62 in 2022, and attaining full retirement in 2027 because it is easier to understand.

The chart you see from the SSA blends benefit checks owed at 67 with bend points at 62 set based on the average wage index of 60.

Tyler Durden

Wed, 10/30/2024 – 18:50