The Fed Pivots (Panics)

Via Tuomas Malinen’s Forecasting Newsletter,

During the past week, we at GnS Economics forecasted that the Federal Reserve will cut by 25bps. Our reasoning was this:

However, the ‘super-core’, measuring services inflation, less energy services, rose by 4.9%, and 0.4% in month-over-month basis. This was the largest monthly increase in the index since April. We assume that this killed all hopes for a 50bps cut next week, because Fed Chair Jerome Powell has described super-core as the “the most important category for understanding the future evolution of core inflation”.

I still stand by this forecast, from a purely economic perspective, because the numbers were clear. Inflation pressures are picking up again. Moreover, retail sales and industrial production came in stronger than expected (0.1% and 0.8% M-o-M). The ‘green shoots’ of the U.S. economy, I reported a week ago, also suggested that the private sector recession may be ending, while risks are abound. The Fed must have seen the improving credit data.

The last time the Fed cut by 0.5% was in October 8, 2008, three weeks after the collapse of the venerable investment bank Lehman Brothers. This was the time when panic was gripping the markets with the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) surfacing with the failure of Lehman Brothers (the crisis had been brewing under the surface since September 2007).

Make no mistake. 50bps cut, is a panic cut. So, why did the Fed panic?

Most likely, there were four reasons:

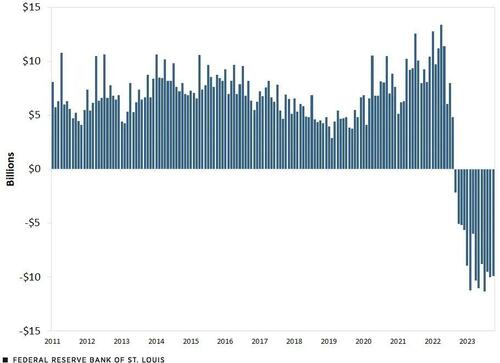

The Fed is racking up massive losses.

Political pressure to not crash the markets before the Presidential elections on November 5 (last FOMC meeting before).

The Federal Reserve is genuinely worried about the economy, but especially about debt levels.

Banking sector fragility.

Like I noted two weeks ago, the Fed is accumulating massive losses from its holdings of Treasuries and corporate bonds. This is because it has bought them when they were much more expensive (rates were lower). When rates rose, the value of Treasuries collapsed, generating heavy losses for the Fed.

Monthly summation of remittances of the Federal Reserve due to the Treasury. Source: Miguel Castro and Samuel Jordan-Wood.

So, the one reason the Fed wants to lower rates (to increase the value of Treasuries) is because it wants to save its own *ss, by increasing the value of the Treasuries it holds. A central bank that holds large quantities of government bonds is never even semi-independent, because their value dictates the credibility of the Bank. The Fed tried to go around this problem by labelling the losses as deferred assets. That is, it marked losses as “assets” in its balance sheet. It is obvious that such blatant accounting fraud can fly only for so long. So, the Fed needed to cut to ease the financial burden, on itself.

Markets were expecting a 50bps cut, and so were some of the politicians. However, in actuality, a 50bps cut may turn up badly for the markets, because it signals that the Fed sees some serious weakness in the economy.

I concluded my last weeks piece by noting:

Banks seem somewhat optimistic and they have eased lending standards. There is not much room for leveraging among corporations and especially among households, though, which shows in the stagnation of borrowing. This indicates that the optimism among banks is likely to be a “false positive”. Their optimism can, for example, be based on the assumption that the Fed easing would create favorable conditions for an economic recovery. Due to the very high level of indebtedness of households and corporations, I consider this to be unlikely. This implies that we could see, possibly a drastic, turn into re-tightening of lending standards and softening of credit demand in the coming quarters.

I think this is the risk the Fed is seeing. There is simply too much private and federal debt and if rates stay high, defaults will start to roll in, with also the likelihood of U.S. sovereign debt rising. This would hurt the economy badly.

U.S. banks continue to struggle under a gargantuan amount of unrealized losses. They arise mostly from the same source as with the Fed, i.e. from Treasuries losing value, en masse. We also noted in the August World Economic Outlook of GnS Economics that the outflow of core deposits seem to have re-started. Deposit outflow is a major risk for the banking sector, because it implies waning trust and, as banking is a business of trust, waning trust implies growing fragility in the banking sector. The Fed cannot stop the outflow of deposits, but it can try to diminish the unrealized losses by cutting interest rates, and hoping that Treasury yields follow. At the time of writing, this was not going well with, e.g. the yield of U.S. 10-year Treasury note shooting up. This is an (early) indication that the bond market now expects inflation to pick up.

Core deposits in the U.S. banking system. Source: GnS Economics, FDIC

Alas, the Fed eased heavily, because of the losses it and U.S. banks are accumulating and because it sees the risk of the economy breaking. These are not encouraging signs.

* * *

P.S. There’s always the possibility that Fed Chair Jerome Powell is a pitiful small man. I don’t believe so, but I of course do not know him personally.

Tyler Durden

Fri, 09/20/2024 – 07:20