China Slashes FX Deposit Requirement To Prop Up Yuan… But Only Delays The Inevitable

With the yuan in freefall, on Monday morning China announced it will cut the reserve requirement ratio on FX deposits by 2% from 8% to 6%, effective September 15th, in a move aimed to stem its currency’s fall. This announcement came after more than 3% depreciation of the USDCNY since mid-August on the back of a stronger USD. This was China’s second FX RRR cut this year – on 25 April, PBOC cut the RRR on FX deposits by 1% from 9% to 8% after CNY depreciated by almost 3% against the USD in one week.

According to Goldman, this cut should help increase FX liquidity onshore, easing FX appreciation (i.e., CNY depreciation) pressures as a result. And while the actual liquidity impact from this cut looks modest by Goldman’s estimates – onshore FX deposits stood at $674BN as of July 2022, so a 2% cut implies $13BN liquidity release – this cut serves as a strong policy signal that the PBOC is uncomfortable with the rapid depreciation of the currency especially ahead of the 20th Party Congress in October; sure enough the USDCNH appreciated slightly immediately after this announcement.

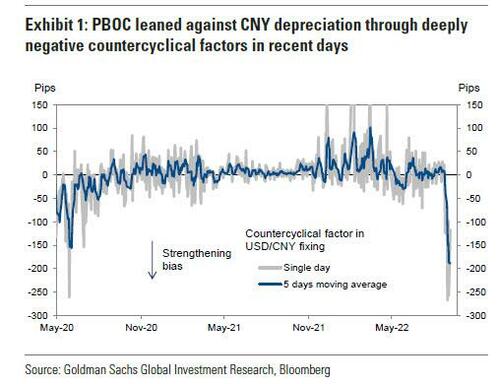

Indeed, as Goldman’s Maggie Wei writes, the countercyclical factor (CCF) in the daily fixing also implies strengthening bias by the PBOC in recent days.

The bank found a similar pattern ahead of the previous 19th National Party Congress in October 2017, when policymakers leaned against CNY depreciation through more negative CCF ahead of the Congress, though policy signals were less obvious going into the Congress in 2017.

Looking forward, Goldman expects USD strength to continue in the near term, and local Covid outbreaks and property weakness to continue to drag on activity growth in China. As such, the bank expects USDCNY to depreciate to 7.0 over a 3-month horizon. After the 20th Party Congress, Wei adds that “policymakers might also have higher tolerance for CNY weakness” – during a press conference this afternoon (September 5th), PBOC deputy governor Liu Guoqiang stated the exchange rate has been more flexible and acting as the automatic stabilizer of both the macroeconomy and the global balance of payments. He added that the exchange rate should demonstrate two-way fluctuations, and not necessarily stick to any fixed number. Goldman agrees, and thinks the PBOC might have tolerance for further CNY depreciation against the USD, especially as the broad USD continues to strengthen, though they might want to avoid continued and too fast one-way depreciation if possible.

Bloomberg’s Simon White agrees and writes that “the forces causing the yuan to decline are structural, and there is a mounting likelihood that China may eventually drop the fixed-exchange rate regime altogether.”

As White adds, Beijing’s FX RRR cut “is unlikely to be enough to countervail the structural problems in China putting pressure on the nominally-closed capital account. China’s response to the economic impact of lockdowns has been to aim stimulus at the predominantly export-facing SOE sector. The result has been a surge of almost $0.5 trillion in China’s trade surplus since 2020.”

Indeed, a look at the underlying drivers of the surplus gets to the heart of China’s main problem: the surplus grew not just due to a surge in exports, but a stagnation in imports. Stimulus in China comes at a cost to the household sector, a net importer. In a sign of the poor sentiment and pessimism in the household sector — driven by financial repression, lockdowns and collapses in property prices — new CNY loan growth for households has fallen to at least 13-year lows.

The bottom line, according to the Bloomberg commentator, is that China’s growth model is broken, as the loss in demand from the household sector is greater than any gain from the export sector, leading to lower growth overall, and thus greater pressure on the capital account. This is enough to push the yuan lower, but China also faces a mounting risk from its heavy debt load. China has had the largest rise in private debt levels since 2010, and its debt-service ratio is through the danger level of 20%.

And while high debt when growth is strong and rising is manageable, it becomes much less so when growth is falling.

There are several levers China can pull to alleviate the growth impact from increased capital flight. One of these is allowing the yuan to weaken. But if the pain becomes too much, White believes that China may choose to abandon its fixed-rate regime altogether, which would have many profound (and dire for the status quo) implications, including for EM monetary policy and global supply chains.

Tyler Durden

Mon, 09/05/2022 – 13:55