Oberlin Faces New Controversy Over Islamic Scholar’s Support Of The Rushdie Fatwa

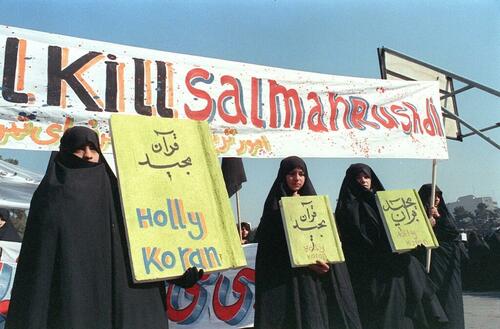

It appears that Oberlin has another major controversy on its hand. For the last couple years, Oberlin has been embroiled in a fight with a small family-owned grocery that it defamed over a shoplifting case involving black students. Oberlin lost $25 million in a record verdict but Oberlin President Carmen Twillie Ambar continued to refuse to apologize. In the meantime, the school seems intent on running the 137-year-old grocery into insolvency as it delays paying on the judgment. Now the school is under fire over a faculty member, Mohammad Jafar Mahallati, who supported the fatwa against Salman Rushdie. The author of Satanic Verses is recovering from a savage knife attack. Hadi Matar, 24, is accused of carrying out the stabbing attack and has expressed support for Iran in the past. The campaign to have Mahallati fired could present some difficult free speech and academic freedom questions.

Mahallati is a professor of religion and Islamic Studies and once served as the Islamic Republic’s ambassador at the United Nations.

According to Fox News.com, Mahallati was asked in 1989 about the “right to put a bounty on someone’s head” and responded “I think all Islamic countries agree with Iran. All Islamic nations and countries agree with Iran that any blasphemous statement against sacred figures should be condemned.” He then added insult to injury:

“I think if Western countries really believe and respect freedom of speech, therefore they should also respect our freedom of speech. We certainly use that right in order to express ourselves, our religious belief, in the case of any blasphemous statement against sacred Islamic figures.”

It was a familiar misrepresentation of free speech values. Islamic countries have long claimed that banning speech or killing those who engage in blasphemous speech is a form of free speech.

The Iranian view of free speech shows the extreme end of the slippery slope of relativism in free speech. We have been debating this increasingly common claim that shutting down speech is free speech. At the University of California campus, professors actually rallied around a professor who physically assaulted pro-life advocates and tore down their display. When conservative law professor Josh Blackman was stopped from speaking about “the importance of free speech,” CUNY Law Dean Mary Lu Bilek insisted that disrupting the speech on free speech was free speech. (Bilek later cancelled herself and resigned after an inappropriate comment in a faculty meeting).

In this case, Iran issued a fatwa supporting the killing of Rushdie and offering a huge reward. Ultimately, two of his translators were knifed, one fatally. Supporting a fatwa is an exercise of free speech. Acting on a fatwa to harm someone is a crime.

Critics, however, insist that Mahallati was a high-ranking official supporting this state action. Nevertheless, I still believe that a professor has the right to voice unpopular and frankly shocking positions in such controversies. I have defended faculty who have made similarly disturbing comments “detonating white people,” denouncing police, calling for Republicans to suffer, strangling police officers, celebrating the death of conservatives, calling for the killing of Trump supporters, supporting the murder of conservative protesters and other outrageous statements. I also defended the free speech rights of University of Rhode Island professor Erik Loomis, who defended the murder of a conservative protester and said that he saw “nothing wrong” with such acts of violence.

A more serious allegation has surfaced over a 2018 Amnesty International report accusing Mahallati of carrying out “crimes against humanity” for covering up the massacre of at least 5,000 Iranian dissidents in 1988. That is conduct or action by Mahallati that would raise grounds over his fitness as a member of a faculty. Yet, he has denied that allegation and Oberlin said that it has investigated and rejected it.

If the school has previously investigated the matter, it should be treated as closed absent new evidence. We recently saw the reopening of an investigation at Princeton as a pretext to fire a controversial faculty member.

On what we know, it would seem that Mahallati would be protected under free speech and academic principles despite his reported anti-free speech views.

Of course, it does not take away from the grotesque position that he has taken. Ironically, his faculty page discusses how he “developed innovative courses with interdisciplinary approach to friendship and forgiveness studies and also initiated the Oberlin annual Friendship Day Festival.” His personal website further states his research is “focused on the ethics of peacemaking in Islam in the context of comparative religions.”

Nothing says ethics and peace more than a lethal fatwa targeting dissenting authors.

As for Iran, it denies any involvement in the attack but added its own sense of offense at being criticized. Instead, it again attacked Rushdie.

Foreign Ministry spokesman Nasser Kanaani said “We, in the incident of the attack on Salman Rushdie in the U.S., do not consider that anyone deserves blame and accusations except him and his supporters.” He added that the West “condemning the actions of the attacker and in return glorifying the actions of the insulter to Islamic beliefs is a contradictory attitude.”

It is strikingly similar to Mahallati’s statement back in 1989. Only in the most twisted view of free speech (and logic) would there be a contradiction in condemning the attempted murder of an author while supporting the author’s right to express his views.

Few academics would support Iran’s blood-soaked interpretation of free speech. However, we need to address the creeping relativism that is sweeping across our campus. A recent poll was released by 2021 College Free Speech Rankings after questioning a huge body of 37,000 students at 159 top-ranked U.S. colleges and universities. It found that sixty-six percent of college students think shouting down a speaker to stop them from speaking is a legitimate form of free speech. Another 23 percent believe violence can be used to cancel a speech. That is roughly one out of four supporting violence.

Faculty and editors are now actively supporting modern versions of book-burning with blacklists and bans for those with opposing political views. Others are supporting actual book burning. Columbia Journalism School Dean Steve Coll has denounced the “weaponization” of free speech, which appears to be the use of free speech by those on the right. As millions of students are taught that free speech is a threat and that “China is right” about censorship, these figures are shaping a new society in their own intolerant images.

It is the subject of my recent publication in the Harvard Journal of Law and Public Policy. The article entitled “Harm and Hegemony: The Decline of Free Speech in the United States.”

Tyler Durden

Tue, 08/16/2022 – 19:45