The Greatest Value Investor You’ve Never Heard Of

By the MacroOps Substack

“We can have no finer role model. First and foremost, he was a value investor — a member of that eccentric tribe that believes it’s better to underpay than to overpay.”

Those words by James Grant were in reference to one of the greatest value investors the world has ever seen. It’s not who you think it is. And no, you couldn’t guess him given fifty chances. This investor remains off the beaten path, absent from many investors’ Mt. Rushmore of allocators.

The investor is Floyd Odlum.

Buried somewhere in the junk drawer of investing lore, Odlum’s story remains unknown. A quick Google search reveals his Wikipedia and IMDB pages. Yet in typical deep-value fashion, the last link on the page revealed Odlum’s investing story.

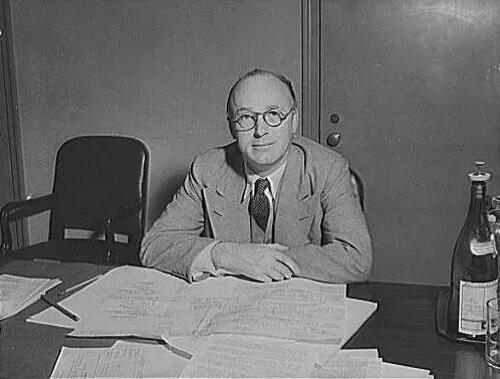

The Holy Financier’s blog post was that last link. The blog proved an excellent springboard for a deeper investigation into Odlum’s early life, initial career and his path to market fortunes. Although Odlum (pictured on the right) and Ben Graham never met, their investment philosophies are one in the same.

We’ll journey through his upbringing, his days as a struggling lawyer and his initial attempt at market speculation. Then we’ll see how Odlum turned $39,000 into $700,000 in two years.

Life Before The Markets

Floyd Bostwick Odlum was born on March 30, 1892 in Union City, Michigan. When Floyd was 16, his father — a Methodist minister — moved the family to Colorado. Floyd stayed close to home, studying law at the University of Colorado. He received his degree in 1914. Floyd bounced around in his first few years after college. After marrying his first wife, Hortense in 1915, Odlum accepted a job as an attorney for the Utah Power and Light company in Salt Lake City, UT.

Three years later, he found himself off the ski slopes and in the throes of New York City. Between 1917 and 1918, Odlum worked for the Simpson, Thatcher and Bartlett law firm, as well as the Electric Bond and Share Company. He settled down with Electric Bond and Share Company long enough to gain the role of vice president.

Dipping His Toes in Speculation

With a decent income from his job as a law clerk, Odlum started trading in the stock market. He initially saw the market as a rich, fertile ground for speculative profits. Far from his cemented legacy as a deep value investor. Yet like most beginning speculators, Odlum too paid his fair share of market tuition.

After losing all his $40,000 starting capital, Odlum retreated from the markets. One newspaper revealed it, “took [Odlum] a while to pay back that sum”. Yet It was this early $40K loss that turned Odlum from speculator to investor. From tape reader to business analysis. Lawyer to Wall Street Legend.

Soon enough, Odlum would be back. The starting capital would be the same. The approach, anything but similar.

The United States Company

Odlum wasn’t just a great investor. He also had a knack for choosing the most generic partnership names, such as his first “The United States Company”. The partnership, formed in 1923, was a couple’s affair. Odlum, George Howard and their wives seeded the partnership with $39,000 ($573K adj. for inflation).

What followed over the next two years was nothing short of incredible. According to Odlum’s biography, The United States Company grew 17x from 1923 – 1925. What started as a small partnership amongst friends turned into a $660,000 behemoth ($9.47M adjusted for inflation).

Odlum’s two-year CAGR is mind-numbing. If that wasn’t impressive enough, he generated these returns while working full-time as a law clerk!

How did he generate such outsized returns?

Well, he was a deep value investor. He searched for fifty-cent dollars and scoured every corner of the market. According to documents from the Eisenhower Library, Odlum preferred two kinds of investments:

Utility stocks

Special situations

He defined a special situation as “an investment […] involving not only primary financial sponsorship, but usually also responsibility for [the] management of the enterprise.” The former lawyer wasn’t interested in flipping a business for a quick buck, either.

Embedded in Odlum’s strategy was the determination to see a special situation through until success, “[We will] stay with the investment until the essentials of the job have been done, and then move on [to] another special situation”.

Between 1925 – 1928, Odlum steadily grew the partnership. By investing in utilities and special situations, The United States Company AUM grew to $6M (over $88M adjusted for inflation). It was around this time that Odlum began sensing euphoria in the market. He smelled a top and he decided it was time for him to act.

The Formation of Atlas Corporation

In 1929, he rolled his original partnership into a new vehicle, The Atlas Corporation. Wary of a market top, Odlum sold half his assets. He stayed in cash and issued $9M worth of Atlas Corporation securities. With $14M in cash, Floyd sat on his hands. Waiting for the next market crash, which shortly followed.

Odlum was prepared and took full advantage once fear had fully gripped the market and there was blood in the streets… His subsequent operations were chronicled in an old newspaper article (courtesy of NeckarCap on Twitter):

“After the crash, Odlum, looking around quietly with more ready money than almost anybody in Wall Street except [a] few of the big banks, noticed that the trend in trusts had reversed.”

Odlum’s 1929 Strategy: Sit. Wait. Attack.

Along with his traditional investments, Odlum dabbled in a number of other industries, including:

Mining

Oil and gas

Motion picture production and distribution

Aircraft and airlines

Department stores

Manufacturing

Broadway stage productions

Hotels and buildings

But his bread and butter during the Depression was buying investment trusts. His strategy was simple. He found investment trusts that had fallen so much their stock prices were trading less than the value of their marketable securities. A good example of this in today’s markets is Manning & Napier (note: I do not hold shares).

He discovered he could buy these trusts, liquidate their assets, and reap large profits for his stakeholders. He was buying dollar bills for $0.60 and he milked this strategy for all it’s worth. He ended up buying and merging investment trust twenty-two times. The newspaper article profiled these dealings:

“He figured out that by buying all the outstanding shares of a particular trust, he was really buying cash or its equivalent at sixty cents on the dollar.”

When he didn’t have the cash to buy the trusts, he sold shares in his own company, Atlas, to fund the purchases. After exchanging his stock for the trust’s stock, Odlum would merge or dissolved the existing trust, keeping the cash and assets within Atlas Corp.

This strategy helped grow his assets to $150M ($2.2B adjusted for inflation).

Between 1929 and 1935, Odlum invested (and controlled) many diverse businesses. He owned Greyhound Bus, a little motion picture studio named Paramount, Hilton Hotels, three women’s apparel companies, uranium mines, a bank, an office building, and an oil company.

Taking It All In

Odlum started with $40,000 and lost it all speculating in the market. He then pooled together another $39,000 to form his first partnership. That original $39,000 grew to $150M in controlled assets. All that during a span of just twelve years.

The math is incredible. Odlum grew assets 384,515% in a bit over a decade. That’s a 32,042% CAGR for asset growth.

And his early partnership returns are just as impressive. Odlum grew assets from $39,000 to $6M between 1923 – 1929. That’s a cumulative 15,284% return. In other words, Odlum compounded capital at an annual rate of 2,547%.

Life After Markets: A Love of Aviation

Odlum’s life was unique. His extracurriculars sprinkled with high-profile relationships, a pioneer wife and bountiful philanthropy. After his divorce in 1935, Odlum married Jacqueline Cochran. Cochran (pictured below) was a pioneer in the field of women’s aviation. And while Amelia Earnhart garners most aviation lore, Cochran’s track record is nothing to scoff at. Some of her achievements include:

Flying solo on the ninth day of flying lessons

First woman to complete the Bendix race, a cross-country race from LA to Ohio

Set flight duration record in 1937 flying from NY to Miami, FL

First woman to make a blind landing (1939)

Broke 2,000km international speed record (1940)

The list goes on. At the time of her death, Cochran held more speed, distance and altitude records than any living pilot.

Odlum played a key role in women’s aviation and space flight. He financed a majority of his wife and Earnhart’s flights. He also pumped millions into the US missile development program because, “I think the money could have been spent better otherwise. But it’s too early to tote up the value of its products. My wife thinks the moon shots were terrific.”

Health and Retirement

Odlum battled rheumatoid arthritis most of his adult life. The pain got so bad he had to stop working. Yet even in retirement, Odlum conducted business. One section in Odlum’s obituary shines light on his relationship with business:

“He often [took[ telephone calls on a rubberized receiver while floating in his Olympic-sized swimming pool.”

Odlum entertained (and housed) some of America’s most prolific leaders and talents. He dined with General James Doolittle, Bob Hope, Gloria Swanson, Walt Disney, Nelson Rockefeller and Howard Hughs.

But of all these guests, none were more famous than President Dwight D. Eisenhower. He and Eisenhower shared a close relationship. So close, in fact, that Odlum carved out a piece of land for Eisenhower to live during the winters. Eisenhower’s small piece of property on the Odlum Estate was known as Eisenhower Cottage.

Bringing It Back To Investments: Three Takeaways

I want to finish this essay with three takeaways from Floyd Odlum’s investing career:

You don’t need to be 100% invested 24/7

Boring is beautiful

Be a dumpster diver (with standards)

1. You Don’t Have To Be 100% Invested 24/7

Odlum wasn’t a market timer. He was a deep value investor. When value ideas dried up, Odlum went to cash. He didn’t force investments or lower his underwriting standards. He simply sat in cash.

Jesse Livermore, a man whose made (and lost) millions in the markets, praises sitting on cash. Seth Klarman is known for his 40% cash balances during periods of market froth.

If you want to beat the markets you must do things differently. Passive investors are 100% invested, but they’re not worried about beating the market.

2. Boring is Beautiful

The United States Company invested in utility stocks and special situations. These are boring corners of the market. Yet it’s these areas that catapulted Odlum’s returns into the stratosphere. How can we apply this ‘boring is beautiful’ philosophy?

In today’s tech-driven market, many investors forget about the boring, slow-growing cash producers. These companies are toll road operators, electrical component producers, road builders. Boring businesses with not-so-boring returns.

3. Be a Dumpster Diver (with Standards)

The stocks Odlum bought were the ones others hated. These companies traded around 52-week and all-time lows. You wouldn’t find anyone talking about these stocks at cocktail parties.

Yet they offered outsized returns simply because nobody bothered to look at the (potential) hidden value. Be a dumpster diver with standards. You’ll find many companies trading around all-time lows that aren’t as bad as Mr. Market thinks.

Sources Used:

https://www.eisenhowerlibrary.gov/sites/default/files/finding-aids/pdf/odlum-floyd-papers.pdf

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Floyd_Odlum

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/e85e/5bb20ac461ed6ef05a5fa0590bab214fd3ef.pdf

http://theholyfinancier.com/floyd-odlum-deep-value-investor-never-heard/

Tyler Durden

Sat, 08/06/2022 – 16:30