Return Of “Go-Stop” Fed Will Lead To Sky High Rates

By Simon White, Bloomberg Markets Live Commentator and reporter

The Federal Reserve in the 1960s and 1970s vacillated between responding to inflation and employment, leading to volatile business cycles, rampant inflation, and weak growth. This so-called “go-stop” approach is akin to today’s environment, and led in the 1970s to the Fed initially underdelivering on rate rises, which then forced it to over-compensate with the eye-watering 20%-rates of the Volcker era in the early 1980s.

The 70s have several differences to today’s environment, but there are a number of key similarities that make the lessons worth heeding. For a start, the late 1960s — when the seeds were sown for the Great Inflation of the 70s — resemble today’s backdrop.

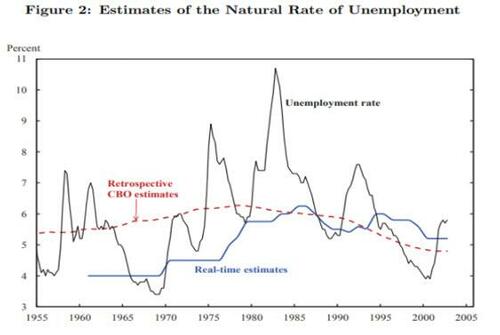

Back then, the Fed underestimated the so-called NAIRU (non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment) meaning it thought it had more room to ease than it really did. Real-time estimates of the NAIRU were over a percentage point lower than retrospective estimates.

Political pressure from the LBJ and Nixon administrations to pay for social programs and the Vietnam War kept Fed policy easy while the budget deficit was allowed to swell to the widest since the WWII. That combination was highly conducive to the genesis of runaway inflation in the 1970s.

That inflation is blamed on many things — Nixon closing the Gold Window in 1971, the Arab oil embargo in 1973, the ending of the Nixon price-wage controls in 1971-74, among others — but in reality those were just kerosene on a fire that had already been lit due to excessively loose monetary and fiscal policy.

The Fed has made the same mistake under a different guise in the current cycle. Over the last two years, the Fed moved to average inflation targeting and a commitment to maximum employment. Rather than underestimating NAIRU, the Fed jettisoned the concept altogether! It openly stated it would “over-loosen” if necessary to achieve full employment.

That’s reminiscent of the “go-stop” central banking of the 60s and 70s. The Fed would keep policy loose in the “go” stage of the cycle, until the public became concerned about inflation. Then it would move to the “stop” phase of tightening policy until rising unemployment became a concern.

Today we have already had the “go” phase, and now we are entering the “stop” phase as political concern grows about the “cost of living crisis”.

However, the Fed is likely to lose its nerve in the face of slowing growth and financial-market volatility, the same way it lost its nerve when it said inflation was transitory, only to see it accelerate to almost 8%. Unemployment will begin to rise, and the political pressure will be on the Fed to revert to “go” mode again.

This we saw in the 1970s when then Fed Chair Arthur Burns began to re-loosen policy in 1974 in response to rising unemployment, even though the embers of inflation were still glowing. Inflation came back with a vengeance in the second half of the decade, and was not finally tamed until the sky-high rates of the Volcker era in the early 1980s.

There is a similar risk in this cycle of seemingly tamed inflation re-rearing its head, and rates having to be jacked significantly higher — causing a deep recession — as political pressure to temper prices eases, the mid-term elections pass and unemployment begins to rise.

Arthur Burns oversaw the Great Inflation of the 1970s, but it required a Paul Volcker to crush it. Like a general fighting the last war, Jay Powell is unlikely to be the man who finally slays today’s inflation demon.

Tyler Durden

Fri, 03/25/2022 – 19:00ZeroHedge News