EU Steps Back From Impractical Russia Oil Embargo: Kemp

By John Kemp, Senior Market Analyst at Reuters

EU leaders have stepped back from imposing an immediate embargo on Russian crude and petroleum product imports as the impracticality of the policy has become clear. Imposing an immediate embargo on Russia’s fossil fuels “from one day to the next would mean plunging our country and the whole of Europe into a recession,” Chancellor Olaf Scholz told German lawmakers this week.

Russia’s exports of crude and petroleum products to Europe are the second largest bilateral flow of oil between any two trading partners in the world, behind the United States and Canada, according to data from BP.

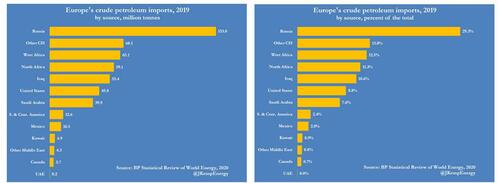

Russia supplied 29% of Europe’s crude imports and 51% of the continent’s petroleum product imports in 2019, the last year before the pandemic (“Statistical review of world energy”, BP, 2020).

No other trading partner came close to Russia’s share, which would make it extremely hard to replace in the short term.

So even speculation about a possible ban drove oil prices sharply higher this week, as traders weighed the practical difficulties, before prices retreated as it became clear EU policymakers were backing away from the idea.

New Oil Order?

Some embargo advocates have suggested the EU could ban Russian petroleum imports, then encourage the redirection of international flows to minimize the net loss of supplies from causing a spike in prices. In this scenario, sanctioned Russian crude would be left to buyers in China and India, freeing up crude from the Middle East to be delivered to refineries in Europe.

On the product side, Russian fuel oil and distillates could be sent to South America, Africa and Asia, while Europe takes more unsanctioned products from the United States, China, India and the Middle East.

But there are multiple serious obstacles to making this work, which is likely why it has been deferred for the time being.

For producers and consumers, supply routes would become much longer, increasing the number of freight tonne-miles, pushing up demand for tankers and raising transport costs significantly. More importantly, crude oils are only semi-fungible. Most refineries are optimized to work with specific qualities of oil. Swapping Russian and Middle East crudes would reduce efficiency, raising costs and prices.

Redirecting flows would disrupt long-standing customer and contractual relationships. Middle East marketers have invested time and effort building long-term relationships with refiners in China, India and the rest of Asia. Asia is perceived as the growing market of the future, while Europe is the declining market of the past, especially with its plan for an accelerated transmission to net zero emissions.

Breaking long-term contracts and giving up Asia’s lucrative growth markets to supply refiners in declining Europe, possibly only for a few months or years, would make little strategic sense. Similarly, North America’s refiners have lucrative and semi-captive markets in Central and South America they will be reluctant to swap for Russia’s markets in Europe.

For refiners in Asia, there is little incentive to disrupt long-term relationships with secure Middle East suppliers to become dependent on Russian exporters if those exports might be subject to extraterritorial U.S. and EU sanctions later.

Complex Web

Crude and product flows around the world form a dense interconnected network or matrix. Forcibly reprogramming Russia’s exports via sanctions implies changes to all the other supplier and customer relationships. For commercial reasons, most crude exporters and refiners send to the nearest available export market and buy from the nearest suitable source of imports.

Until now, Russia has overwhelmingly supplied Europe, the nearest major importer, though flows were slowly being reoriented to Asia, the fastest growing market, even before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. For the same reasons of distance, Europe has purchased most of its imported crude and products from Russia and other countries in the former Soviet Union.

The political imperative to end these flows and co-dependence is now in conflict with the commercial and geographical reasons to maintain them. Political imperatives may prevail but they are unlikely to do so quickly. In 2019, Russia’s exports to Europe accounted for more than 6% of all the world’s traded crude and more than 8% of all its internationally traded products, according to data from BP. Reprogramming such an enormous share of world trade in the space of a few weeks or months would create a huge upheaval.

Tights as a Drum

Global oil markets were tight before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine with inventories below the pre-pandemic five-year average and trending lower. Even if the imposition of an embargo or other sanctions caused only a small reduction in Russia’s net exports, to deprive the country of revenue, it would still create a high risk of a price spike.

Previous embargoes imposed on Iraq in the 1990s and Iran and Venezuela in the 2010s were offset by extra supplies from other producers, reducing their overall impact on prices. At present, neither Saudi Arabia nor U.S. shale firms appear keen to raise output to offset lost Russian supplies, and the White House has not so far reached agreements to lift sanctions on Iran and Venezuela.

With little spare capacity, EU policymakers have concluded the price risks from embargoing Russian petroleum exports are too high, and have backed away from the idea for now.

Tyler Durden

Sat, 03/26/2022 – 08:10ZeroHedge News